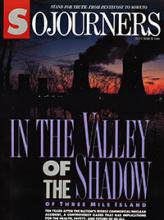

The accident at Three Mile Island on March 28, 1979, was followed by a decade of decline for the nation's nuclear power industry. But despite tremendous cost overruns, gross mismanagement, climbing interest rates, and slumping demand - factors that together would wipe out most businesses in a matter of months - nuclear power is still hanging on. It remains on a life-support system, namely the U.S. government, which has refused to pull the plug on the dying industry.

Meanwhile, it is the public, not the U.S. government, that is left with the bill, as the utilities that own the nuclear facilities attempt to hike their rates to recoup their billion-dollar losses. And it is the public that is left with a potential public health disaster - due to the effects of accidents, routine emissions of low-level radiation, and the mounting radioactive waste from the plants - that could have life-threatening implications for all of us.

The Reagan administration did everything in its power to try to jump-start the struggling industry. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), the agency set up to ensure public health and safety, essentially became an activist for nuclear power during the Reagan era. Just after Bush was elected in November, the Reagan White House (the one that promised to "get big government off the backs of the people") quietly issued a couple of executive orders that significantly expand federal control over the civilian nuclear power industry.

One of the executive orders gives the federal government the authority to assume control of a civilian nuclear power plant in the case of a "national security emergency," further blurring the distinction between civilian and military reactor use (long championed by the U.S. government as part of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty).

Read the Full Article