“WAIT—IS THAT Mr. C?” one of my students asked incredulously. “THAT’S MR. C?” he repeated, making a motion of his head exploding.

The rest of the class was reacting the same way, and I couldn’t help but laugh as I confirmed that, indeed, the person profiled in the documentary we were watching—a man serving a 35-year sentence for second-degree armed robbery—was indeed “Mr. C” (Charles Rodgers), the co-teacher of our class (via video) for the past two months.

Unbeknownst to them, my students had just concretely experienced the lesson with which we started the semester: Don’t judge a person by a single story.

The consequence of a ‘single story’

ACCORDING TO AUTHOR Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, there is great danger in a “single story.” The single story makes a single experience, characteristic, or action in a person’s life “become the only story,” and the only story, in turn, “creates stereotypes.” More important, Adichie says, when we make one part of a person’s incredibly varied life, experiences, and decisions the only story, “It robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar.”

I’ve been teaching Catholic social justice to high school students for nine years. My course always includes guest speakers, documentaries, and movies in which people can tell the fullness of their whole story. The full story allows students, in Adichie’s words, to recognize our “equal humanity” and to emphasize how we are similar. In Christian terms, the revelation of another person’s dignity allows for the possibility for conversion which, in my understanding, allows us to see the truth of another’s situation from a position of equality and solidarity, not judgment (whether positive or negative).

Adiche’s assertion was the perfect lens through which I could approach my Catholic social justice class last fall because, by pure chance, I could teach the single-story concept in practice as well as in theory. I was already set to do an in-depth interview with Charles “Boston” Rodgers—the so-called Mr. C—whose story is told in the documentary Serving Life. The film tells the story of a hospice program, for which Rodgers volunteered, at Angola state prison in Louisiana, and it’s a resource I use for the criminal justice unit of my class. Rodgers was released from prison in 2018, and I “met” him last year when he had a video conversation with my students after they watched the documentary.

However, for the fall semester, I wanted the new group of students to get to know Rodgers in a broader way, apart from the single story of the crime he committed and his subsequent incarceration, before they watched the documentary.

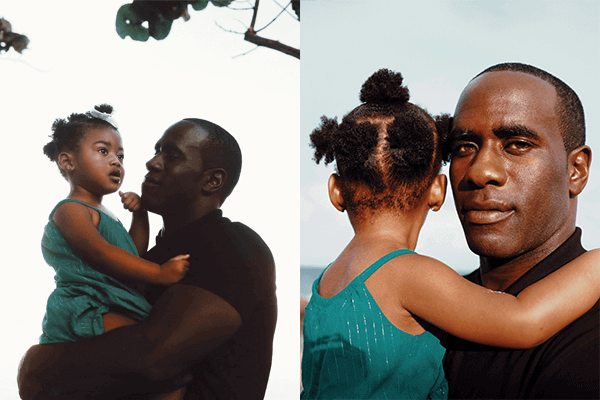

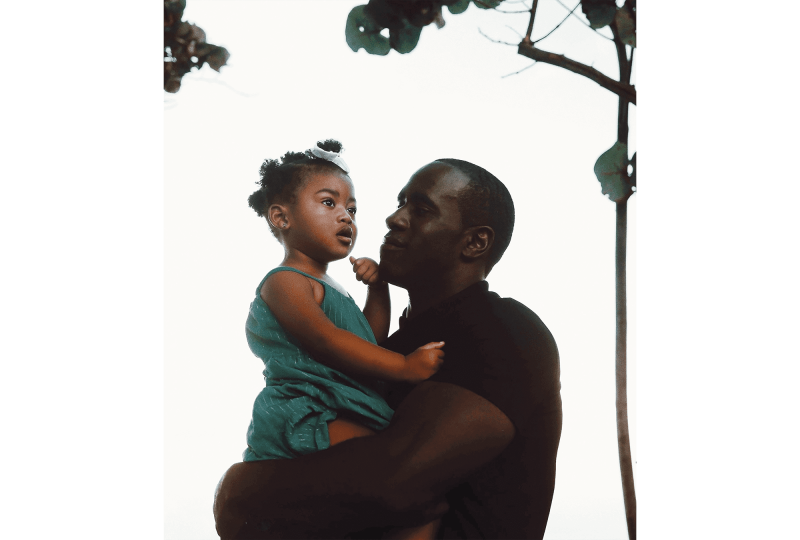

At the beginning of the semester, I introduced Rodgers to the class as a co-teacher, telling them about various aspects of his life—a college graduate who holds a bachelor’s in Christian ministry and counseling; an African American man raised in difficult circumstances; someone working as an HVAC tech who’s the father of a baby girl. Students enthusiastically asked questions about topics ranging from his favorite sports teams and colors to his opinions on immigration law and racism. Already the students had a more complex idea of Rodgers, beyond that of a person who served time in prison, about which they were still unaware. Rodgers told me he was looking forward to working with the students:

For me, [co-teaching the class] was a way to take my attention off myself, because I was away so long that I have to make up for lost time. I have to get myself established in a way that other 39-year-old men are already established. I’m catching up on that. So, focusing on helping students helps me distract myself from my problems and allows me to do something for others. I thought of it as “hospice” on the outside—a way to do something for others.

Although I was accomplishing my goal with the students, unknown to me, I was entering every part of my partnership with Rodgers with my own single-story biases, which kept revealing themselves as we got to know each other.

‘A trap for people like me’

RODGERS’ 35-YEAR SENTENCE for robbery (unusually long for such a crime) was based on a single story of his adolescence, the story of the so-called serial juvenile delinquent. In and out of jail from age 13, he eventually ended up with 14 arrests.

The other stories of his life lend more complexity to his juvenile record. “Probably half” of his juvenile arrests, he said, were due to assault charges against his mother’s then-boyfriend. He was defending his mother from physical abuse and his sisters from sexual abuse. Those stories were not told at his sentencing. Nor was the fact that, due to his mother’s drug abuse, he was “in and out of foster care, starting at age 5,” including some situations that “were just horrible”—even some that involved family members. He talks about one particularly vicious 15-year-old cousin who “loved to torture me. I still don’t know why. I was 5 years old and staying with them because of my [mom’s drug habit]. Once, my cousin pushed me out the window—I fell 40 feet and broke everything. I was in the hospital for weeks,” he remembers. During his childhood, he was sent to at least 10 foster homes.

Despite the academic success Rodgers would later achieve in prison—he completed a GED, technical training in two trades, and a bachelor’s degree, and he also tutored other inmates—his high school record tells a different story. He told me he was disengaged and had “behavior issues.” Rodgers said, “I couldn’t focus because I was so fixated on what was going on at home.” One time, as a freshman in high school, he fell asleep in class after another late night protecting his mother from his stepfather. His teacher reprimanded him: “She told me I’d be ‘just another statistic.’ Looking back on it, she was probably trying to reach me through ‘tough love’ or something. The problem was that’s the only love I had ever had.” The teacher’s negative approach had a profound effect; Rodgers never returned to high school.

Rodgers talks about the traumas he experienced as a child—from his drug-addicted mother and a father who has been incarcerated his whole life (Rodgers has never met him) to a dangerous neighborhood and poor schools—as contributors to the “school to prison pipeline.”

I first realized that prison was a trap for me, and a lot of people like me—minorities who come from neighborhoods like the one I grew up in—when I read The Road Less Traveled by M. Scott Peck. It talks about who is statistically more likely to go to prison or go to college or whatever based on their environments. That was a huge realization. I know now that the system penalizes Blacks more harshly than whites—longer sentences, more traffic stops, etc. In my experience, it’s done maliciously and vindictively.

Rodgers’ insight is reflected in the data: The United States currently incarcerates approximately 1.8 million people, or about 650 people per 100,000. The system is notoriously biased against minorities; according to the Sentencing Project, “Black men are six times as likely to be incarcerated as white men, and Latinos are 2.5 times as likely. For Black men in their thirties, about 1 in every 12 is in prison or jail on any given day.”

We talked about who bore the responsibility for Rodgers’ situation. In my view, it was a social failure that didn’t prioritize resources for Rodgers and for his family. But Rodgers rejected my analysis. He made it clear that this was my own single-story lens, one that failed to take in the complexity of his actions.

“At first, I blamed the world and took no responsibility,” Rodgers said. “I was angry at what I was born into—I didn’t ask to be here—my mother being what she was, and my father being what he was.” Therefore, “crime wasn’t difficult for me, because I felt like the victim.” He began breaking into cars and taking things from people “because I felt the world owed me.”

rodgers_spot_a_tinypng.png

After an armed robbery charge in Louisiana, Rodgers jumped bail. When his best friend was shot and killed, Rodgers said, he and his friend’s brother went to seek revenge on the rival gang who had murdered him. When Rodgers was arrested, he was armed, and he said he was fully prepared to take that revenge. The arrest, in Rodgers’ view, thus saved lives—including, perhaps, his own.

Developing tools other than violence

DURING RODGERS’ FIRST three years in prison, he racked up more than 40 write-ups for violent behavior and served a third of the time in solitary. But, despite his growing awareness of the inherent corruption and bias in the criminal justice system, Rodgers said that prison gave him chances to change his life—chances born as much of pure luck as of his hard work.

When Rodgers was sent to prison at age 20, he immediately began filing motions for appeals. At first, he paid another inmate in Little Debbie Honey Buns to do the paperwork, but he soon mastered the legal process and was able to write his own motions, paying inexpensive lawyers to sign and file, using money he earned by building furniture and other crafts in the prison woodshop.

After a while, Rodgers began to experience a change in focus. His penchant for challenging the authority of the prisoner hierarchy and prison staff not only got old but, recalling the fights, he said, “It hurts!” He observed that “the smarter prisoners studied human behavior and learned how not to fight” while still maintaining respect. “I had to learn to be somebody I had no idea how to be because I never saw them growing up.” He wanted to be educated, patient, trustworthy, and responsible; he wanted to use self-control and the power of his intellect instead of violence. He used all the tools available to him: classes, books, and the presence of professionals who frequented the prison to teach and volunteer. “I put myself wherever ‘free people’ were in the prison and mimicked their behavior,” he said.

Part of his motivation to change came from the fear and anger he felt receiving a 35-year sentence as a terrified 20-year-old. “I felt worthless, like my life had no value,” he said. At the same time, though, he “wanted to prove the judge and everyone wrong” and to show them that he was not worthless. “It was a gradual, painful process,’” Rodgers said. “When I got treated like a human, it made me want to be humane, and when I was treated like an animal, I acted like an animal.” But he did not give up, encouraged by his successes and the small freedoms and trust he was able to achieve. He gained more responsibility, such as volunteering with the hospice program at Angola, editing the prison newspaper, and being able to create in the woodshop.

His amateur attempts at filing an appeal remained unsuccessful until, by chance, a benefactor who had seen the Serving Life documentary agreed to pay excellent lawyers (at a total cost of approximately $20,000 to $30,000) to take on his case. In July 2018—after several appeals, a look at his full history, including his record in prison, letters of restitution to victims, and victim support for his release—he was discharged after serving 17 years. He is now father to a 2-year-old girl and makes a living as an HVAC technician and salesperson.

rodgers_spot_b_tinypng.png

Finding a way in a failed system

RODGERS IS UPFRONT about the sheer corruption and bias of a criminal justice system that made it easy for him to end up in prison, and equally forthright about the fact that, although it was deeply unjust, the 35-year sentence is what forced him to take his situation seriously. For Rodgers, both facts are true:

Was it a harsh sentence? Yes. Maybe I lied to myself and thought it was a good thing, because I wouldn’t have taken it so seriously if it was less time—like if it was three years, I would have been released and gone back [to my old life]. It took that long for me to come to terms with, one, I wasn’t the victim and, two, I needed to be there. I came to accept that I did a lot of dirt.

The temptation of the single story, as Adichie attests, is that it becomes the whole story. But the full story is always far more complex and demands much more complex solutions. In Rodgers’ view, reform should start with intervention and prevention programs for young people at the first sign a child is having problems, such as bad grades or behavioral issues. If he had had that possibility, his story may have turned out different. But Rodgers sees opportunities for change at every step in the process—before involvement in the criminal legal system, before sentencing, during and after incarceration. “The system failed in that it didn’t give incentives to improve—on a 35-year sentence, the max amount of good time I could get off my sentence was six months.” Nevertheless, amid the systemic injustice, he found a way:

I manipulated it in my favor—I tricked myself to believe it was something good, though I knew it was borderline slavery, working for 4 cents an hour. I was at Angola, which was where the slaves from Angola landed. It was formerly a slave plantation. I was angry because I realized I let them put me back in slavery. Prison wasn’t great, but I made it what I needed it to be to maintain my sanity and obtain my freedom.

Rodgers is painfully aware that the “freedom” he’s obtained is only partial. Even though he has worked full time since his release and has excellent credit history and financial means, he still has difficulty renting an apartment because of discrimination based on his incarceration, let alone getting a mortgage to buy a condo or being certain of his right to vote.

My students came to know a multifaceted, complex person with a variety of life experiences. But society still judges Rodgers by the single story of a past conviction. It’s up to all of us to learn a better way.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!