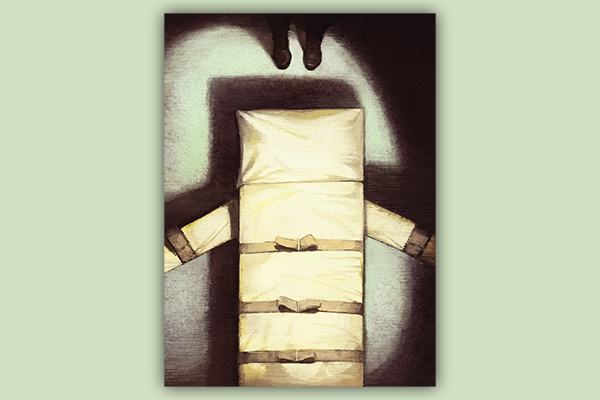

I HAD A friend. He died last summer. Actually, to say “He died,” is too passive. He was killed. He was killed as I held him, as those who loved him and those he had hurt watched. On June 26, 2024, the state of Texas executed Ramiro Gonzales for the rape and murder of Bridget Townsend. In 2001, Ramiro was 18 years old, suicidal, violent, and struggling against the chains of addiction; but 23 years later the state took the life of a 41-year-old man who was sober, faithful, and deeply considerate of everybody who surrounded him. He was loved. I miss him terribly.

Ramiro and I first connected in 2014 as pen pals. What started as an exchange of letters blossomed into a friendship spanning more than a decade. There are some who only knew Ramiro for the vicious violence he perpetrated. I’m sympathetic to their anger, but this is not the Ramiro I came to know. As our friendship deepened, Ramiro cherished my children, sending them birthday cards and artwork. We shared in both the sacred and mundane of our daily lives. We also discussed his crimes, his grief, and his profound shame.

After entering the order of ministry in the United Church of Canada, I became Ramiro’s spiritual adviser. This designation allowed me to be with him in the execution chamber, my hand on his chest, singing and praying over him as Texas used a lethal injection of pentobarbital to kill him. It was one of the most haunting and devastating experiences of my life. Not a day goes by when I don’t think about Ramiro, about Townsend, or about everything that went wrong that brought us to that deadly day.

Just a few years ago, the thought of me — a Toronto pastor — sitting inside a Texas death chamber would have seemed unimaginable. Yet, there I was, due to a significant shift in Texas’ execution protocol. The state had moved from allowing only its own appointed chaplains to accompany the condemned in the moment of their execution to granting inmates the right to the spiritual adviser of their choice, a result of years of legal battles over questions related to religious freedom and equity. My journey to that chamber was also defined by the moral dilemma of opposing capital punishment, while simultaneously taking on a vital role within the execution process of someone I cared for deeply.

swan2.png

Sacred duty or state function?

IN DECEMBER 1982, Rev. Caroll Pickett was preparing for Texas’ first execution since the Supreme Court’s reinstatement of capital punishment in 1976. As prison staff rehearsed their roles for the nation’s first lethal injection, Warden Jack Pursley assigned Pickett the task of greeting the inmate, Charlie Brooks Jr., as he arrived at the Huntsville Unit. Pickett recounts Pursley’s instructions in Within These Walls: Memoirs of a Death House Chaplain, “Talk to him. Listen to him, comfort him as much as you possibly can. But, above all else, I want you to seduce his emotions so he won’t fight.”

This marked the beginning of the modern era of the complicated relationship between religious clergy and the state of Texas when it came to the death penalty. State-employed chaplains had a dual and often conflicting role of providing spiritual care and comfort to the condemned while ensuring they remained calm and compliant during their final moments. This duality helped ensure the execution process ran smoothly for staff and witnesses, reinforcing the sanitized illusion of lethal injection as a “humane” way to carry out death sentences.

After 95 executions, Pickett retired, and Rev. Jim Brazzil served as Huntsville Unit chaplain for the next five years. While he earnestly worked to assure the condemned of God’s love for them, Brazzil was also acutely aware of his function within the execution process. Years later, Brazzil would sit down with Swedish journalist Carina Bergfeldt to share his experiences accompanying prisoners within the death house. In the resulting book, A Good Day to Die, Brazzil describes his first meeting with the new unit warden: “What we need is for him to die. ... Do whatever it takes to keep him calm; that’s your job here. Do it in a way that meets his needs and ours.”

This protocol remained largely unchanged for decades. When the time came for an inmate to move to the chamber, the chaplain would accompany them, guiding them on how to place their body as the guards prepared to strap them down. Brazzil would place a hand on the prisoner’s leg, giving a small squeeze to let them know they weren’t alone. While certain elements of the execution process evolved — such as shifting executions to 6 p.m. instead of midnight and allowing victims’ families to witness — the chaplain’s role remained relatively consistent: Provide spiritual comfort to the person facing execution and ensure they don’t resist.

Evolving spiritual roles

IN MARCH 2019, Patrick Murphy waited in a holding cell, hours past his scheduled execution, as the Supreme Court deliberated over his religious rights. A Buddhist, Murphy was challenging a Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) policy that only allowed state-employed Christian and Muslim chaplains inside the execution chamber.

After the tense delay, the Supreme Court ruled in Murphy’s favor: Texas could not execute him unless his Buddhist spiritual adviser — or a state-provided equivalent — was allowed in the chamber. Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s concurring opinion offered two options: allow all inmates to have a representative of their faith present in the execution chamber or restrict all religious advisers to the witness room. Texas chose the latter.

Murphy and his legal team kept fighting. When his execution was rescheduled for November 2019, Murphy argued the policy remained discriminatory, as TDCJ chaplains could stay with inmates until the chamber door closed, while outside spiritual advisers were forced to leave hours earlier. A federal judge agreed, staying Murphy’s execution. Murphy remains on death row, awaiting a new execution date.

In 2020, Ruben Gutierrez’s request for a Christian chaplain at his execution was denied, with the state citing security concerns. The Supreme Court stayed his execution to assess the validity of those claims. The next year, John Henry Ramirez sued after TDCJ denied his request for his pastor, Rev. Dana Moore, to lay hands on him and pray aloud during his execution. Hours before his scheduled execution, the U.S. Supreme Court granted a stay and later ruled 8-1 in March 2022 that denying such religious practices likely violated federal law. Ramirez was executed on Oct. 5, 2022. Rev. Moore was permitted to touch him and pray aloud, establishing a significant precedent for religious accommodations in executions.

A letter that changed everything

IN EARLY 2021, I opened a white envelope bearing the familiar stamp of the Alan B. Polunsky Unit, home to all of Texas’ male death row prisoners. Ramiro had received a new execution date, and his attorneys were pursuing multiple legal avenues, including his request to have the spiritual adviser of his choice with him in the execution chamber.

“I have placed you down as my spiritual adviser,” he wrote, “What does this mean? This means I have requested the state allow me to have you ‘present’ — that is, physically present in the death chamber if I am being executed — and performing the usual hand-on-the-chest thing while praying.”

Uncertain about what this meant, I sent a text to one of Ramiro’s attorneys. Texas wasn’t allowing any clergy in the death chamber — not even chaplains. Surely, they would not allow a foreign pastor who openly opposed the death penalty to be present during an execution.

“What are the chances Texas would actually allow me to accompany Ramiro?” I asked. His attorney replied, “I think the chances are zero.” I wrote Ramiro back, agreeing to serve as his spiritual adviser. It’s easy to say yes to something you don’t believe will happen.

Meanwhile, Texas was quietly working to adjust its execution procedure. By April 2021, the state published a new protocol allowing inmates to choose a spiritual adviser to accompany them in the chamber. The adviser would need to pass a background check, be properly accredited with their denomination, and could not speak to or touch the inmate. This limited physical presence represented a seismic shift in TDCJ policy.

To my surprise, after completing the required background check and submitting my credentials, I was approved to accompany Ramiro inside the execution chamber. By the time I made my way to Texas to begin our final visits in June 2024, the state agreed to grant Ramiro every spiritual accommodation he had requested: For my left hand to rest on his chest, for my right hand to hold his, and that I pray aloud as he was killed.

On the one hand, I felt relief that Texas wouldn’t deny Ramiro the spiritual presence he so desperately wanted. On the other, one less thing to litigate meant the state was closer to taking his life.

Silent support

ONCE THE PAPERWORK was approved and the orientation scheduled, I finally had the space to reflect on what I had agreed to do. I wasn’t anxious about being present as Ramiro died — I had accompanied others in their final moments. But the circumstances of how he would die were uniquely horrifying. Back in 2016, when he received his first execution date, I had agreed to be one of Ramiro’s witnesses, determined that the last face he saw would be one of love.

Officially, I’d be present as a volunteer of the state, but I was intensely opposed to what Texas was preparing to do. Every fiber of my being rejected it. Still, I knew I wouldn’t disrupt the execution. Ramiro wouldn’t have wanted me to. What he desired most was for me to stay by his side, in that tiny, oppressively green room that has seen hundreds of others like Ramiro struggle to maintain dignity within a process designed to deny it.

As the execution date approached, I became increasingly aware that no matter what I did, I would leave the chamber carrying some form of moral injury. If I spoke out against the injustice of execution I would be forcefully removed, leaving Ramiro to die alone. If I stayed silent, would I be complicit with the state taking his life? Was I any different than the state-employed chaplains, with my calming presence only making it easier for Texas to kill someone? These questions followed me into the chamber and remained after I returned home to Canada, my family, and my congregation. Moral injury, I’ve learned, is a wound that defies easy healing.

swan3.png

Bearing sacred witness

IN THE MONTHS after Ramiro’s execution, I asked other advisers who’d been permitted in the execution chamber how they navigated what I had experienced as a spiritual and ethical dilemma.

Sister Helen Prejean, a leading advocate for the abolition of the death penalty, has served as spiritual adviser to several condemned men over the past four decades. In 1997, she was present in Virginia’s execution chamber to pray with Joseph O’Dell, though she was forced to leave before the lethal injection was administered. In February 2024, she accompanied Ivan Cantu to his death, holding his hand and praying directly into his ear as Texas carried out his execution. I asked her if at any time she struggled with being there. “[There was] no conflict,” she answered without hesitation, “because I was absolutely there to be there for him. Absolutely for him. And it was very clear — I’m praying into his ear and helping him through it by holding up his dignity. And he knew that I was doing all I could.”

After a relationship spanning nearly 25 years, eucharistic visitor Jennifer Rogers accompanied Arthur Lee Burton during his execution in August 2024. Burton and Rogers had extensive conversations about what he needed from her within the chamber. “I feel like I would have betrayed him if I had gone in there and surprised him with some political or theological statement denouncing the process when that’s not what he asked me to be there to do,” Rogers told me.

While Rogers’ focus was on being present for Burton, she noticed how the depth and sincerity of their connection seemed to affect the Huntsville Unit staff. “So I thought, okay, well, that’s just God flowing through all of us in very strange and different ways.” Listening to Rogers made me wonder if witnessing her bond with Burton might prompt the staff to consider the inherent humanity of those lying on the gurney. If she loved Burton — and if I loved Ramiro — deeply enough that the loss was so tangible, perhaps that might mean something to those with eyes to see.

Sister Prejean describes the spiritual adviser’s role as one of witness as well as accompanier. “People never get close to this. ... So when we become a witness, we have a call to help change this thing, not to passively say, ‘Oh, this is sad. I was with him. I did my best.’” While I had been worried about being complicit in the moment, Prejean spoke of the adviser’s responsibility after the execution. She sees it as a moral obligation to share what we have seen in the death chamber with the aim of changing hearts — and ideally, political resolve in ending for good state-sanctioned killing.

The power of love and presence

I STILL WRESTLE with the dissonance between my mind, which holds the tension of being present for my friend even amid violence; my body, which carries the trauma of that awful day; and my soul, which weeps as I watch the modern-day crucifixion play out over and over again. It is not a dilemma unique to conversations about capital punishment. Christ often moves within morally complicated spaces. If we can stand in those places of death, confident in the truth of our shared humanity, and reflect that truth back to those who surround and defend the gurney, perhaps that is where cracks in the system will finally begin to emerge.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!