A BRAID OF sweetgrass sits next to my laptop. When I get overwhelmed by an endless to-do list or the weight of living in the Anthropocene, I run the strands through my fingers like prayer beads and bring the braid to my nose. Big breath in. Big breath out. Even after years of doing this, the scent carries a grounding sweetness, reminding me of something deep and good.

In her iconic book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer, an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi nation and professor of environmental biology, writes that when you take in the scent of the sweetgrass, or wiingaashk in Ojibwe, you “start to remember things you didn’t know you’d forgotten.”

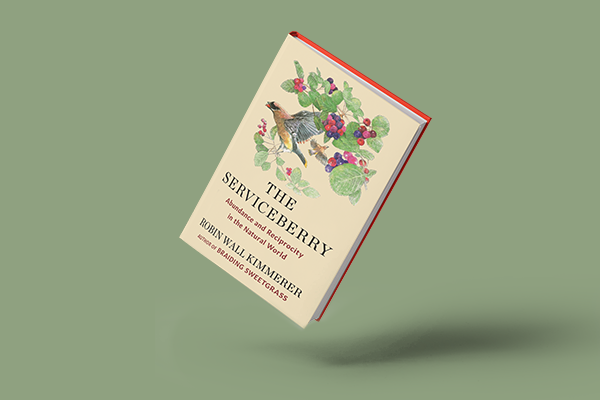

In her latest slim volume of essays, The Serviceberry, Kimmerer helps us remember what we have clearly forgotten: The world is a gift, and there is plenty of the world for everyone and everything.

Known for its beautiful white blossoms and abundant, nutty-tasting fruits, the serviceberry, also called juneberry, is named bozakmin in Potawatomi, meaning “the best of the berries.” To Kimmerer, the serviceberry is the embodiment of the gift economy. “In a serviceberry economy, I accept the gift from the tree and then spread that gift around, with a dish of berries to my neighbor, who makes a pie to share with his friend, who feels so wealthy in food and friendship that he volunteers at the food pantry,” Kimmerer writes. “To name the world as gift is to feel your membership in the web of reciprocity.”

Read the Full Article