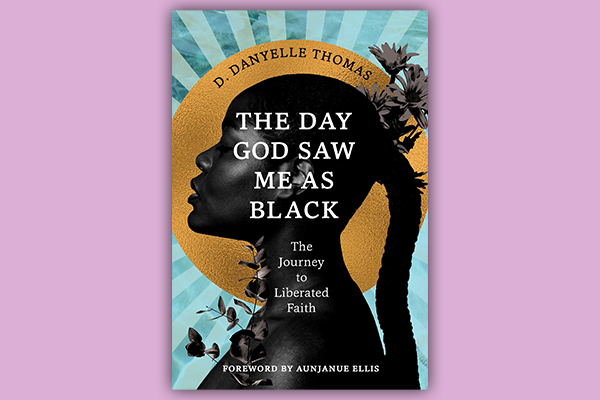

“I’LL BREAK IT down so that it may forever remain broken: Blackness is holy in and of itself,” writes D. Danyelle Thomas in her new book, The Day God Saw Me as Black: The Journey to Liberated Faith.The founder of the digital faith community Unfit Christian reflects on the ways that white evangelical theology has shaped the Black Church. She lovingly calls in the Black Church to liberate our mindsets around race, gender, sex, and sexuality.

Like Candice Marie Benbow’s Red Lip Theology (2022) and Lyvonne Briggs’ Sensual Faith (2023), The Day God Saw Me as Black reflects Thomas’ identity as a Black millennial womanist. Her experience growing up as a fat, Southern, Black Christian woman is central throughout.

Thomas expresses her love for the Black Church, even as she names all the ways it has been colonized and shaped by white evangelicalism — a Christian tradition “plagued by racism, sexism, classism, trans- and homo-antagonism, and systemic oppression.” These are the evangelical values, Thomas explains, that insisted “God is good all the time,” even amid violence and oppression, from the transatlantic slave trade to South African apartheid to the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Read the Full Article