CHARLES SCHWARTZ is a professor of physics at the University of California at Berkeley the sponsoring institution of the Lawrence Livermore and Los Alamos nuclear weapons laboratories. Schwartz has been active for years in raising questions about the complicity of scientists with the military and the nuclear arms race.

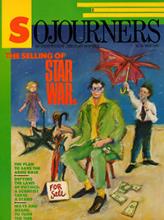

Most recently he has been an outspoken opponent in the science community of the Star Wars program. In addition to signing the "Anti-SDI Pledge," a commitment signed by almost 7,000 scientists and engineers to boycott SDI research, Schwartz announced last year that he would refuse to teach physics major degree courses as a further act of non-cooperation with the arms race. Schwartz was interviewed in March by Danny Collum.

-The Editors

Sojourners: Let's begin with some of your personal history. How did you end up in the physics profession?

Charles Schwartz: Probably like a lot of other people in the sciences, I got into that line of study early in my educational career and got locked into it pretty thoughtlessly - I was good at it and it seemed exciting.

I was an undergraduate at MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] in the early 1950s, and I stayed there to get my doctorate in physics. Then I came to California and was on the faculty at Stanford University for a brief period. After that I got a position on the faculty at the University of California at Berkeley, where I've been since 1960.

In the early part of my career, I was a pretty standard academic, interested in my research first, in teaching second, and in the rest of the world hardly at all. But being in Berkeley in the late '60s, I learned from and responded to the activism and the criticism about the role of science in relation to war, the role of this university in particular, and the role of my profession.

Read the Full Article