SINCE THE ASCENDANCY OF JOHN PAUL II TO THE PAPACY, numerous battles have been fought between Rome and local Catholic churches that object to the pope's attempts to roll back the reforms begun by the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. Many churches have suffered casualties, including those in the United States and Brazil, among the most powerful in the Catholic world.

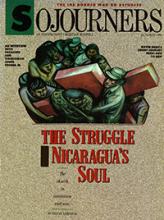

But perhaps the most tragic case is Nicaragua, where religion has become another source of division in an already polarized nation. Instead of providing solace during a time of war and great suffering, the Catholic--and Protestant--churches have wasted their energies in persecuting members who do not conform to the leadership's ideological convictions, particularly as regards the contra war. As has frequently occurred in the past, when churches have allowed themselves to become political tools, politics has distorted the Christian message.

There are no winners in the Nicaraguan story, for--as pointed out by a U.S. missionary with long experience in the country--the mass of the people are so confused by the bitter struggles between anti-government bishops and clergy and pro-government priests and nuns that they "don't know to whom to give their loyalties anymore."

While the contras are (and will be) a lost cause, the outcome of the religious conflict is less certain. Some high-ranking Sandinista officials believe it could cause the government more damage than the contras ever inflicted, because it involves churches that affect Nicaraguan attitudes toward the Sandinistas and the government's image abroad.

On one side are the government and its supporters in the Catholic and Protestant churches; on the other, the Catholic hierarchy and the fundamentalist evangelical churches. Both sides have strong backing in the United States, Latin America, and Europe.

Read the Full Article