My people have committed two sins: They have abandoned me, the spring of living waters, and have dug for themselves cisterns, broken cisterns ... that hold no water.

—Jeremiah 2:13

IN THE LATE 1980s and early '90s, Palestinians rose up against the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories in what became known as the First Intifada. Instead of acceding to the demands for justice by the "children of the stones," the response was a process of talks that led to the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993.

The “peace process” engaged the leadership of the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization)—then weak, corrupt, exiled, and with little vision or support—in what turned out to be a worse-than-fruitless effort that led to the perpetuation of the occupation and suffering of the Palestinian people, and which made a just peace even further away.

The process was intriguing to many of us in the peace and justice community, and it successfully co-opted us, as it co-opted the Palestinian leadership, but this process entailed both the abandoning of principled positions and the adoption of the Oslo system, a broken system that could not possibly deliver what it promised.

We were treated to a new language by Israel and the U.S., which seemed at first blush to adopt our own slogans: Where Palestinians were constantly complaining of Israel’s refusal to acknowledge them—its demonization of their leadership, and trying to have Jordan or other local collaborators speak on their behalf—the new process brazenly invited the PLO itself and its leader Yasser Arafat to participate as the “sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people.”

The fact that the PLO was not allowed to speak on behalf of two-thirds of the Palestinian people (the refugees in exile) or for those who were citizens of Israel was not initially clear, and Yasser Arafat was exalted as a leader beyond reproach. His own failures in the area of transparency and his undemocratic actions were politely overlooked, as were the failures of Yitzhak Rabin, his Israeli counterpart, since both were viewed as men of peace, and we wanted to give peace a chance by giving them room to maneuver rather than stubbornly insisting on principles.

The slogan of “direct negotiations,” a very legitimate idea, was also turned on its head. The negotiations process neatly sidestepped international law, the United Nations, and European and Arab countries and allowed Israel to negotiate directly with the PLO with no involvement from any third party. In effect, it provided a forum for the wolf and the sheep to work out their culinary relationship with no outside interference.

The continuing human rights abuses and the illegal settlement activities were also downplayed, since these issues were supposedly actively under negotiation, and it was deemed necessary to give both parties an opportunity to work out their differences. People of goodwill, both inside and outside the area, were urged to support the peace process and help the moderates engaged in it against the extremists who were trying to derail it.

Meanwhile, the negotiations lent legitimacy not only to existing settlements and their expansion but to the creation of a sophisticated structure of two separate systems of life, one for Jews and another for Arabs in the occupied territories, with separate roads, schools, health systems, social security, courts, and police, and not merely different laws and separate living quarters for the two communities.

The slogan of a Palestinian state was also co-opted with the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA), which was given some of the trappings of a state without any of its powers or sovereignty. In fact, the PA was specifically designed to serve as a subcontractor for the occupation to control its own people on behalf of the occupiers, while beholden to the Israelis and the donor community for its own salaries.

How did this happen?

The truth is that these early days were very heady and exhilarating days as we, and I include myself, witnessed the handshake on the lawn of the White House, saw the Nobel Peace Prize given, and heard our very own slogans repeated as official policy of the U.S. State Department. We were no longer “voices crying in the wilderness” or marginalized, unrealistic idealists but invited, honored guests in the hallways and corridors of power and decision-making.

The price of toning down our principled criticism, accepting some measure of “realism,” and making concessions in order to give peace a chance seemed a small enough price to pay. The alternative seemed to put us in the camp of rejectionists, extremists, and radicals who did not believe in peace at all and who were bent on hatred and enmity. So we went along and, before we knew it, the trap snapped shut and we were caught.

In fact, as extremists from both sides continued to practice and preach violence and even assassinated Rabin, we became even more invested in the “peace process” and in seeking ways to salvage it or help it survive. In other words, the broken cisterns became our own.

So how were the cisterns broken? And why could they not deliver the outcome they promised? We need to understand the mechanisms of the peace process to appreciate why the cisterns were fundamentally broken.

First: A process was created (the Oslo Framework) that was both divorced from principles and organs of international law and the international community and that also declared itself to be the one and only proper forum for discussing and resolving the conflict. Any attempt to appeal to international organs, the United Nations, or other bodies was specifically prohibited by the terms of the Oslo process.

Similarly, attempts to engage or involve third parties (or indeed for the Palestinian people to be involved in any anti-occupation activity) would also be viewed as contrary to the peace process. No mechanism was created to enforce compliance with the agreement, so Israel could and did regularly violate its terms (such as allowing free passage between Gaza and the West Bank), but Palestinians were strictly held to their obligations under it, and Israel had a variety of sanctions available to penalize them for doing so.

Second: The process accurately reflected the power relationship between the parties and was specifically engineered to grant the powerful party clear advantages and to maintain the dependence and weakness of the weaker party. Under the terms of the signed agreement, issues of concern to Israel (such as security, control of borders, settlements, etc.) were specifically relegated to its sole authority and control. Issues of concern to Palestinians, however, were relegated, instead, to joint committees where Israel had veto power.

The Palestinian Authority was therefore required on a daily basis to submit to the joint committees requests for everything from permits for people’s travel to the supply of water, fuel, and electricity, to imports and exports, to designating radio frequencies for broadcasting—everything! Even customs and import duties for West Bank goods were collected by Israel (with 25 percent withheld for “administrative services”) and turned over to the Palestinian Authority only if the PA remained on good terms with Israel. When cooperation between Palestinians and Israelis broke down, the PA was paralyzed.

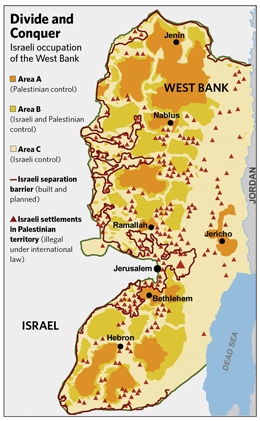

Third: The Palestinian Territories were divided into noncontiguous parcels labeled A, B, and C. Area A (comprising the densely populated cities and towns) was under the control of the Palestinian Authority; Area B (mostly villages) was under joint Israeli-Palestinian control, with the PA having responsibilities in civil matters and Israel in security matters; and Area C (about 62 percent of the West Bank)—containing all the settlements, the Jordan valley, and all the empty land in between—was under full control of Israel and its civil administration.

The theory was that the powers of the PA would gradually increase both in substance and territory as more land was transferred from C to B and then to A, ending up with a fully sovereign Palestinian state.

Fourth: Within the areas “ceded” to Palestinian control, the PA was essentially required to act as subcontractors for Israel and serve its interests, especially in security matters. The PA was required to control its population and provide continuing security cooperation with the Israeli forces. Where the PA failed to act sufficiently, Israel permitted its forces frequent incursions and forays into Area A.

The Palestinians had correctly decided to end armed struggle against the occupation and to cooperate in preventing attacks against Israel, yet Israel (and sometimes the PA) viewed this as requiring them to end all forms of struggle as well. PA police officers were required to prevent Palestinians from moving to points of contact and friction with Israelis for purposes of demonstrating, and when Palestinians acted politically in ways Israel did not like, the PA police were accused of failing in their assigned functions under the agreements.

Fifth: The process was an integral part of Israel’s ideological policy of hafrada (separation). The model of “they are there and we are here” was first readily accepted even by the peace community in Israel and elsewhere as a form of self-determination and neighborly coexistence. When security cooperation between the PA and Israel broke down with the Second Intifada, which began in 2000, this philosophy was reinforced with the building of the separation wall, which confirmed in concrete terms the policy of separation between Israel and Arabs in the West Bank and Gaza.

Each of these elements—all basic ingredients of the Oslo peace process—run contrary to notions of justice, reconciliation, and peace. They serve the Israeli goals of the occupation, fragment the Palestinian people, foster discrimination, co-opt and shackle their leaders into a subservient role, and legalize and legitimize the continuing occupation, while blocking as illegitimate all avenues of working toward a just solution. A “peace process” built on these principles necessarily would fail to produce justice or peace, and serves only to perpetuate and legitimize the occupation.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!