“REJOICE IN THE LORD ALWAYS.” “Do not worry about anything.”

“I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.”

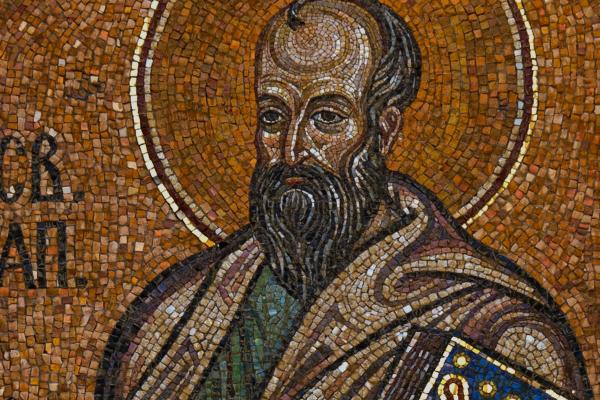

Verse fragments such as these, in the midst of a warm, fuzzy letter the Apostle Paul wrote to the house churches in Philippi, sustained me through high school and beyond. Indeed, the entire letter is saturated with joy. Philippians has been a source of great comfort to many Christians over the centuries.

It is clear that Paul had a close friendship with the believers in Philippi. A major purpose of the letter was to thank them for sending one of their own, Epaphroditus, with a gift for Paul. Sadly, the messenger became very ill while with Paul, but now that he has recovered, Paul is returning him to Philippi, along with the letter (2:25-30; 4:15-18).

Less clear are the political assumptions and harsh realities that frame this encouraging missive. Paul lived and traveled within the mightiest empire the world had known up to that point. He carried his gospel message thousands of miles on Roman roads built for military conquest. At the same time he challenged the very foundations that supported this empire, and his activism was perceived by political authorities as a threat. Paul paid for this by suffering in a Roman prison (1:13) and did not know if he would survive his ordeal or not (1:21-24).

Read the Full Article