Now I heard there was a secret chord

That David played and it pleased the Lord,

But you don’t really care for music, do you?

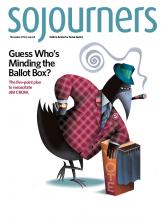

It is said that Leonard Cohen’s song “Hallelujah” has been covered more than 300 times by various artists since its 1984 release. Perhaps one of the reasons it has endured is because of the stories it tells about tragic biblical figures such as King David, who was simultaneously murderer and a “man after God’s own heart.”

Inspired by her son, who played an arrangement of “Hallelujah” on the harp for his bar mitzvah, Geraldine Brooks explores the profoundly paradoxical character of David in her novel The Secret Chord (paperback edition out this fall). Brooks’ unwillingness to resolve this paradox invites readers into the story to wrestle with the categories of good and evil and the nature of repentance. After the dust settles, however, readers will find that it is not the depth of David’s repentance but the abuse of power that defines his kingship.

The timeline in Brooks’ novel roughly spans David’s early ascent to power through his death and Shlomo’s coronation (Brooks uses the transliteration of the Hebrew to spell names, for example Shlomo instead of Solomon). Drawing upon the tradition that the histories of 1 and 2 Chronicles were written by the prophet Natan, David’s story is told from the perspective of the prophet. During the first battle that David is not on the battlefield with his men, the frustrated, middle-aged king commissions Natan to write his biography, so that David’s descendants may know “what manner of man” he was. David gives Natan a curious list of people to interview, including individuals that David knows will be severely critical of him, such as his estranged wives and brother. This narrative detail—like many others in the novel—serves as an explanation for scripture’s curiously flawed portrait of Israel’s most powerful king.

Read the Full Article