THE WORD “PROPHETIC” gets thrown around a lot in Christian circles. The adjective carries both an ancient heft and a forward-looking fire, the perfect jolt of biblical energy for the nouns that need it: a prophetic book, a prophetic sermon, a prophetic Instagram infographic. But living prophets, especially the self-anointed ones, aren’t so easily marketable. They’re stubborn and strange, somehow arrogant enough to believe they speak for an invisible God who turns out to be, more often than not, extremely angry at large swaths of humanity.

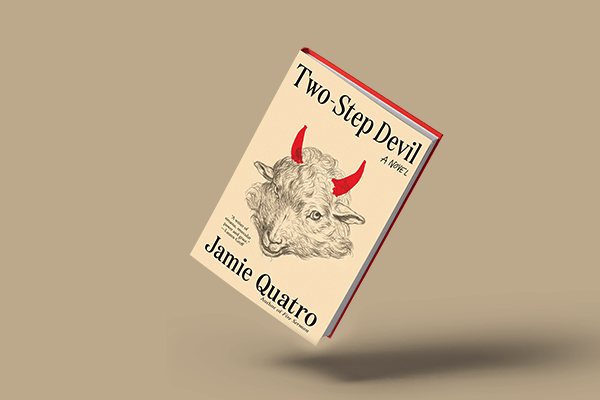

Two-Step Devil, the second novel of rising literary voice Jamie Quatro, places one such character in the contemporary South. Known simply as The Prophet, Quatro’s lonesome protagonist lives in the kudzu-entangled backwoods of northeastern Alabama, where he paints visions of impending holy war on junkyard scraps. He’s the kind of person who can “walk around behind the world’s curtain” — glimpse the spiritual stakes behind the drudgery of familiar, if fragile, social conditions. After rescuing a teenage girl from a sex-trafficking scheme, he’s confident he’s found the one who will deliver his apocalyptic message to the White House. While he’s frail and tormented by self-doubt, she’s young and, in his eyes, innocent. Meanwhile, the girl, Michael, must pull off an urgent mission of her own.

Read the Full Article