WHEN RAHIEL TESFAMARIAM was 5 years old, she and her mother flew from Eritrea to New York City, arriving in the United States with six-month tourist visas to help prepare for Tesfamariam’s eldest sister’s wedding. After the six months had passed, Tesfamariam’s mother began packing clothes for a return trip to Eritrea, but Tesfamariam adamantly refused to leave. Tesfamariam’s brother recalls being at the airport and watching their mother step to the gate; Rahiel stepped back and said, “Bye, Mommy.” And so it was: Rahiel Tesfamariam remained in the United States in the care of her siblings, out of the shadow of the Eritrean War of Independence, with an expired travel visa.

The rest of her story could be told this way: She became a legal permanent resident of the United States, graduated from Stanford University, became the youngest-ever editor in chief of The Washington Informer, received her Master of Divinity degree from Yale University, and launched Urban Cusp, an online community for Black millennials interested in the intersection between faith, culture, and justice. Tesfamariam worked as a columnist for The Washington Post; led #NotOneDime, a national Black Friday economic boycott during the 2014 Ferguson protests; and was named by Essence magazine as one of its “New Civil Rights Leaders.” She got married. She became a mother. It could be said that Tesfamariam pulled herself up into the American dream.

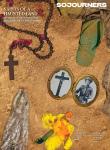

Tesfamariam’s book Imagine Freedom: Transforming Pain into Political and Spiritual Power (Amistad), released earlier this year, tells that story, but with a difference. Telling only that version, like the American dream itself, would be insufficient. Tesfamariam spoke with Sojourners associate editor Darren Saint-Ulysse in April about how she carries Africa within, political power’s ephemeral nature, and God’s command to free the captives. — The Editors

Darren Saint-Ulysse: You have a long history of social activism. What made you want to write Imagine Freedom now? How did you decide what to include?

Rahiel Tesfamariam: I was not necessarily trying to convince myself I have a story worthy of telling — but what part of the story needs to be told? What takeaway from the story is so important that the world needs to know? The takeaway was initially rooted in capitalism, careerism, and the American dream. But later it evolved into how I divorced the American dream.

Imagine Freedom comes out of a clear understanding that healing was the most important story I could ever tell. When you think about Black resilience, the story is often threaded with trauma and suffering. So I asked: What have we done to survive this long? What kept us? We call ourselves resilient people, but what has made us resilient? How did we survive? What happened to us for 400 or 500 years? We’ve unpacked the trauma, but we didn’t unpack the survival strategies and the emotional, spiritual, and psychological stories.

Imagine Freedom is a compact, condensed version of how I unpacked diasporic healing rituals. How did Africa survive despite colonization? How did Black Americans survive despite enslavement? Why were the forces so strong, persistent, adamant, and determined to destroy us? We don’t often look at white supremacy as a form of spiritual warfare against us, one that we must arm ourselves against and resist. It’s not just a system; it’s also a spiritual war.

Then there’s also my “beautiful story”: Coming to this country from the slums of Africa, undocumented, not speaking a word of English, having nothing, and then going to Stanford, Oxford, and Yale; traveling the world; writing for The Washington Post. I fell in love with that story. I was like, “Hey, anybody who wants to, listen to this great story I got to tell you.”

Eventually, I had to learn that my résumé doesn’t tell the most important parts of my story. The most important parts of my story are the things to this day that I won’t talk about. It’s the stuff that I wasn’t saying. Not my victories, but my trauma. Now I understand that what makes me so great isn’t what I accomplished. It was never Stanford or Yale. It was a little girl refusing to die, refusing to have her spirit broken. This little girl refusing to let a war define her destiny, but to say instead, “I belong on this land. I got purpose on this land.” And being able to say that at age 5.

In my 30s, I began to ask: What is it that this little girl knew that I don’t know? What clarity did that 5-year-old girl have about herself that this 30- and 40-year-old woman doesn’t have? How do I trace back to her? We always think liberation is a forward journey toward freedom. Sometimes, it is retrieving what they took from us. I had to go back and fetch that 5-year-old girl.

darrenfeature.png

From 2016 to 2019, you spent three years on sabbatical in southern Africa. “I knew Africa had changed me,” you wrote, “and I was terrified that I would quickly slip back into old ways of being.” How do you carry southern Africa within you?

To paraphrase Kwame Nkrumah, What does it mean for Africa to be born within us? I had to figure out what it means for Africa to be not a chain, medallion, or ring I wear.

I had a powerful conversation with a friend who talked about Malcolm X’s hajj to Mecca. He said that Malcolm returned renamed. He was given more than one name. We know El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz, but he was also given a Nigerian name. As he traveled to these countries, they would give him a name in the local tradition. It was how he adopted pieces of all these places. That renaming practice is very important because it signifies a new identity.

But I already had an African name, right? I went over there as Rahiel Tesfamariam. So, what was my renaming going to be? It can’t be the jewelry or the African print. It’s got to be the personhood. How I was going to look, sound, move, pray, dance, breathe differently because Africa had become so embedded in me that they’d look at me and say: “She don’t sound the same.”

I believe, in my core, that is what happened. For three years, I lived and studied with South Africans — not just politically, but culturally. The way they danced. Their music. I became obsessed with their culture. What’s so powerful about culture is that culture is liberating. Culture has always been how we have found relief from the oppressor. When I got to Africa, I gave my body more permission to move, more permission to dance. I gained greater freedom in my body.

Freedom is not just ideological; it’s embodied. Africa helped me physically embody freedom. Now, when I see myself on stage, I have a confidence I didn’t have before. Africa gave me permission to be the Rahiel I’d never seen before—and helped me get back to that 5-year-old girl. That’s the greatest gift that Africa ever gave me. It helped me reclaim her.

Your book works with themes of pain and power. What do you mean by “political” and “spiritual” power?

Political and spiritual power have often been considered two distinctly opposite things. I’m beginning to see them intersect in ways I never have before.

We see the political power in the hands [of those] who seemingly are spiritually lacking. And then we see all the spiritual richness in those who have zero political power. So, there’s a way in which we are now questioning what true power looks like.

We always thought power was about who we put into office. It was about the presidency, about local officials. We are living in a moment when we recognize we can have all of that in place, have all the ducks lined up — even have the “right party” in place — and still we see some of the worst acts of brutality ever witnessed with our own eyes. Then you get to a place where you say, maybe it’s not about political power. Maybe it’s about not giving the enemy power over our souls. It is not about which Pharaoh we pick. It’s about whether or not Pharaoh is in our mind. If Pharaoh controls our mind, then it doesn’t really matter anyway. Before, a lot of freedom fighters thought you had to come for the vote. But I want the minds. I want the hearts.

What is inspiring your imagination now?

Palestine, without a doubt. I am so deeply inspired by the people of Gaza, the people of Palestine. They’re helping me imagine a new world.

I don’t know if the world has ever been on the same page as we are now; that the old must die away and the new must be born. Thank God for the digital era we are in, where they can’t gaslight us the way they used to. Before, the narcissists controlled the frame and told us what they needed us to believe in order to do whatever they wanted us to do. Thank God for citizen journalism, for social media, for grassroots media. Kwok Pui-lan talks about “writing back.” Palestine is compelling us to “write back” history.

And those young people standing up in places of privilege: Yale, Columbia, Stanford. They’re inspiring me because those are the sites of empire. Those schools are where the next generation of white supremacists are born; the next generation of capitalists are born. They nearly birthed me into a lifelong capitalist. I know what those places breed. For those young people to be rising up on those battlegrounds is important.

What do you hope that the church gets from reading your book?

There are so many ways that people can’t tell the difference between the body and Pharaoh. There’s a challenge to the church right now: Choose this day which master you will serve. Some of us have, without knowing, bowed down to the idols of our day. God cared a lot about us making a calf of molten gold in the wilderness. And we’ve been doing it for a very long time.

It was God’s own people who did that, because we were mimicking the behavior of our oppressors. There’s a way in which we lived under Pharaoh and within Egypt for so long that we began to think like Pharaoh, move like Pharaoh, talk like Pharaoh. We embraced empire as home. I challenge the church to say once and for all: We know this is not our home!

If this is not home, then how does the church create, cultivate, and sustain a home on earth that welcomes everybody into the fold of liberation? The church has forgotten its command to free the captives. How does that command play out in our sermons? How does that play out in our worship? How does that play out in our fellowship? We have to free the captives. We have to do more than give people a prescription to just get through week by week.

The church is keeping people on life support. And those people want to wake up.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!