SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGISTS USE the term “infrahumanization” to describe the subtle belief that some people are slightly less human than others. This belief is particularly insidious because it goes beyond the scope of individual prejudice and affects how we see entire people groups.

We see this “less human” bias shown in the news cycles focused on the trauma in Gaza. While many of us are dismayed by news reports, we might also subconsciously believe that Palestinians grieve the loss of children and loved ones a little less than we do.

Here in the United States, some medical professionals falsely believe that Black women have a higher pain tolerance. This bias can lead to devastating medical neglect, as Black women die giving birth at a rate two to three times higher than that of white women.

These distortions of humanity can keep many of us parents awake at night. As the father of an Afro-Latino son, I know how some people will see him ... or not see him. I know some will surveil him with suspicion instead of beholding him with tenderness. If we don’t constantly remind him of his belovedness, these distorted mirrors will obscure the beauty of his own reflection.

It takes a deliberate, contemplative approach to examine the way we see ourselves and the way we see others.

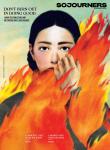

I find essayist James Baldwin’s work instructive at this moment. In his book, Nothing Personal, Baldwin writes: “The longer I live, the more deeply I learn that love—whether we call it friendship or family or romance—is the work of mirroring and magnifying each other’s light.”

For Baldwin, love is the mirror itself. This perspective beautifully shows us that such beholding and healing cannot happen in isolation. We need others to help reflect our light back—through the lens of love. This love will be sturdy and unsentimental, acting on behalf of the misperceived in our society.

The Great Mirror of Love sees us fully and calls us beloved.

Our public discourse and our policy agendas reveal how we see the misperceived and misrepresented. Our approaches can either invalidate people or affirm that we see them in their dignity and full humanity.

Baltimore provides an example of what happens when leaders decide to shift the narrative about communities represented as “dangerous.” This year, Baltimore no longer ranked among the top 10 U.S. cities for violent crime. For nearly 20 years, Baltimore has adopted a program of treating gun violence as a public health problem. Led by a Black mayor, Brandon Scott, the city prioritized fully funding “Cure Violence” models with remarkable success. Through healing-centered strategies and using lived-experience experts in Black neighborhoods, Baltimore has shifted from policies rooted in pathology to ones that projected dignity. A truer mirror was held up to Black boys and their communities—and so far, they have responded.

Ultimately, this work is a larger reflection of the Divine. If we believe every human being bears and reflects the image of God, but the God we image mirrors back exceptionalism, supremacy, or unworthiness, then we’re not encountering Divine Love—a lesser god is at work.

The Great Mirror of Love sees us fully and calls us beloved. And when we reflect that light to one another, we participate in healing both our way of seeing and our world.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!