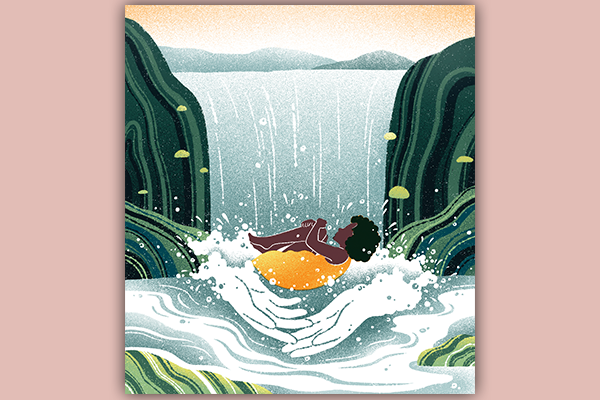

I WAS SWIMMING with friends in a creek when our host led us to a waterfall where a blanket of water dumped into a deep pool. The only way to get to the small cavern behind the fall was to swim below the churning surface. My friends dove under and popped up happily behind the curtain of water. I tried, but the water pounded my back and pushed me back to where I started. The next time, I approached it sideways and reached out my hand for a friend to pull me through.

This memory was fresh when I talked with Ashley M. Jones, poet laureate of Alabama. Her latest book Lullaby for the Grieving is a collection of poems that plumb the depths of grief over her father’s passing as well as grief for the horrors of slavery in American history and ongoing genocide in Gaza.

She told me the title came during a workshop that poet Palavi Ahuja led along the Sipsey River in western Alabama. After a hike, Ahuja asked participants to write a lullaby. For Jones, a lullaby is less about how to get to sleep, and more about “describing where you are ... where you could be and giving you a pathway to pause.”

Read the Full Article