Rigoberta Menchu was a native of Guatemala who had witnessed the worst of that country's genocide against its indigenous population. Her father was part of an indigenous group that occupied the Spanish Embassy in Guatemala City in January 1980 to protest massacres of the Indian people; he died when the military set fire to the embassy. Her mother, also an activist, was tortured and killed by the Guatemalan military, her body left to the dogs in the sight of Rigoberta and her siblings. A younger brother and members of Menchu's extended family were also claimed in the violence.

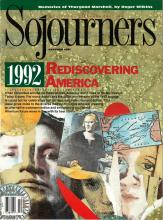

Estimates place the number of Indians killed in Guatemala during the 1980s at 100,000. For the sake of her life, Rigoberta Menchu can no longer live in Guatemala. She serves as a spokesperson for her people, traveling the world, alerting people to the ongoing tragedy of the natives in Guatemala and elsewhere in Latin America, and speaking of signs of hope, such as the growing campaign in response to next year's quincentenary. She was interviewed during a recent visit to Washington, D.C., by Joe Nangle, OFM, who was outreach director of Sojourners when this article appeared. --The Editors

Sojourners: How are your people responding to the 1992 anniversary of Columbus' arrival on your continent?

Rigoberta Menchu: A continent-wide campaign is taking place in Latin America, one which began in October of 1989. The campaign announced that the 12th of October last year was "The Day of Dignity and Resistance Among the Indigenous Peoples." On the occasion of this day, there were activities in all of the countries that are participating in the campaign.

Read the Full Article