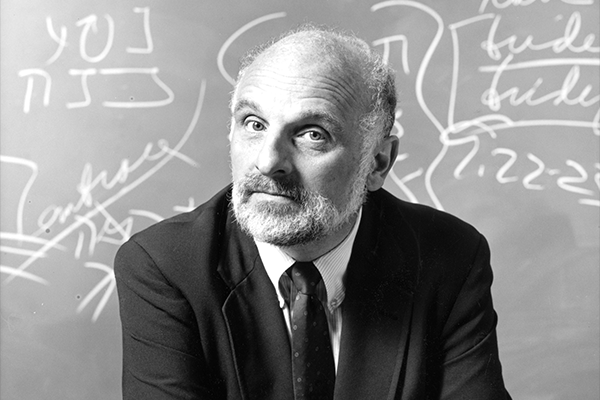

FOUR DAYS AFTER the 2020 presidential election, Sojourners’ then-editor Jim Rice called biblical scholar Walter Brueggemann for his insights on that deeply polarized time, insights that are perhaps more relevant than ever. Their 15-minute phone call on Nov. 7 yielded more of the deep wisdom that Walter had shared with Sojourners since he published his first article with us in 1983. — The Editors

Jim Rice: Where do you think we are and what are we doing as a culture, as a people, and as people of faith?

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login