IN 2000, sophomore Onaje X.O. Woodbine was Yale basketball’s leading scorer and one of the top 10 players in the Ivy League. From the outside it must have seemed like a dream come true for a young man who grew up playing street ball in the Roxbury neighborhood of Boston.

But Woodbine felt isolated and excluded by the white players on the team, troubled by what he’s described as “a locker-room culture that encouraged misogyny,” and hungry to focus on his studies and wrestle with deeper philosophical and theological questions. So he quit basketball.

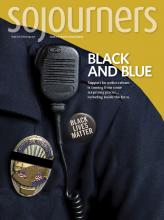

Woodbine eventually returned to the courts of his youth as a researcher, studying the practice and culture of street basketball for his doctoral studies in religion at Boston University. Woodbine is the author of Black Gods of the Asphalt: Religion, Hip-Hop, and Street Basketball (Columbia University Press) and a teacher of philosophy and religious studies at Phillips Academy in Andover, Mass. He spoke with Sojourners senior associate editor Julie Polter in May.

Julie Polter: What led you to study street basketball from a religion scholarship angle?

Onaje X.O. Woodbine: When I was 12 years old, I lost my coach. He was my father figure; I didn’t have my father for most of my early childhood. It was just devastating.

I went to the court the next day to look for him. I felt his presence in that space. It was really the only place, looking back, where I felt safe, I felt whole, where I felt like my inner life was valuable, where there was a whole community whose interest was in my growth as a human being.

Read the Full Article