NEARLY EVERYONE I know is moving. Homes that were once beloved, or at least tolerable, now represent forced encampment. Like rats departing a sinking ship, many of us are running from the wreckage of 2020 with little more than the clothes on our backs and enough money for a security deposit. Change is in the air. Yet, as the adage goes, “The more things change …” Cells renew, but bones remain.

The image on a postcard on my desk, taken by the infamous Carl Van Vechten, is Georgia O’Keeffe next to one of her iconic cow skulls. Her eyes are closed as she cradles the skull in her hand and leans her head against it. The gesture, almost reverent in its grace, seems to acknowledge the animal who once was. The picture is a study in contrast, much like O’Keeffe’s life. According to the postcard, the photo was captured at O’Keeffe’s New York penthouse in 1936. By this point, she’d already made her first pilgrimages to the American Southwest, a region that would provide her with artistic inspiration until her death in 1986. It was also a refuge from the stress of her marriage to the influential photographer and philanderer Alfred Stieglitz. Maybe it’s fitting then that one of the few O’Keeffe pieces I’ve seen in person is related to her attempts to find sanctuary.

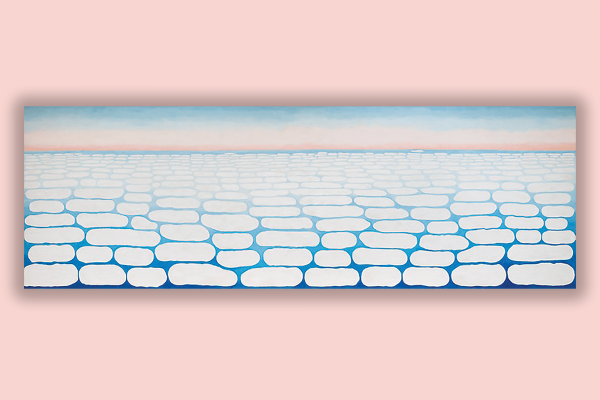

Titled “Sky above Clouds IV,” the painting lives in all its 8-by-24-foot glory at the Art Institute of Chicago. It is primarily composed of, as its title suggests, clouds—clouds O’Keeffe saw as she sojourned across the sky via plane. “Sky above Clouds IV” has mesmerized me throughout the years, largely because it is inescapable. Its ambitious scale invites viewers to sit in an existential space that is ill-defined yet luminous and expansive. Your eyes ride the line of O’Keeffe’s ever-unfolding peach horizon. Time ceases to exist. Perhaps this holding pattern, this sacred spiral, is the present, in which fantasy and reality meet. It could also be a metaphor for the way time functions in nature—quietly, gently, and with little regard for our own schedules or opinions. Although many define O’Keeffe’s work by its latent eroticism, there is so much to say about her exploration of temporality, i.e., the presence of the cosmic and the mundane as sites of renewal and transformation.

I’ve been thinking a lot about John McPhee’s concept of “deep time.” Deep time names geologic time (the assemblage of rock formations, for example) as a way of understanding cycles of nature. These cycles are slower and, in some ways, surer than that of human industrialization. However, an endless line of sky, an animate person holding a relic of death, even a new home can be traced to the impetus of the earth to alter and grow. In O’Keeffe’s work, there is no later, only now. And in the now, the well of enormous time that waters everything, there is room for grief and change and new beginnings.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!