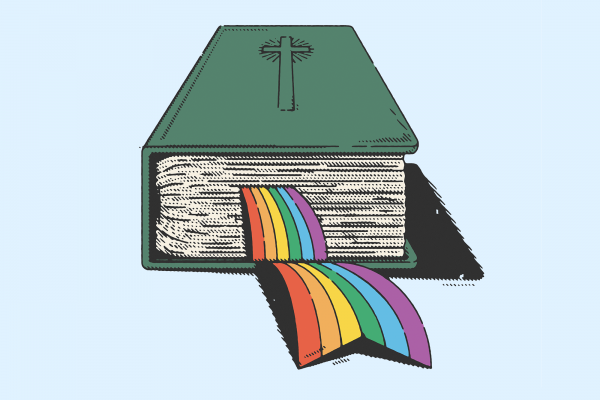

IN JUNE, THE SUPREME COURT held that a Catholic agency can exclude same-sex couples from its government-contracted foster care program, despite a city policy banning LGBTQ discrimination. Assertions of religious freedom carried the day in the narrow ruling of Fulton v. City of Philadelphia; at the same time, broader precedent remains, requiring religious groups to respect generally applicable anti-discrimination laws. The court deferred the deeper challenge of how to square vigorous claims of religious liberty with hopes of inclusion for LGBTQ people.

As people of faith, how do we make sense of these competing claims—for equality and nondiscrimination, bedrock human rights principles, and for religious freedom? For guidance, Christians can look to our own record on religious freedom, theological insight on human rights, and, above all, the ethics of Jesus and Paul.

Let’s begin by affirming that religious freedom deserves its place in the inner sanctum of basic rights. It is a hope that once emboldened persecuted communities to flee Europe and helped inspire the allied struggle against fascism. It remains indispensable for religious minorities the world over—like the Iranian Christian seminary student who fears grave persecution, or Sikh and Jewish communities suffering violence in this country.

Read the Full Article