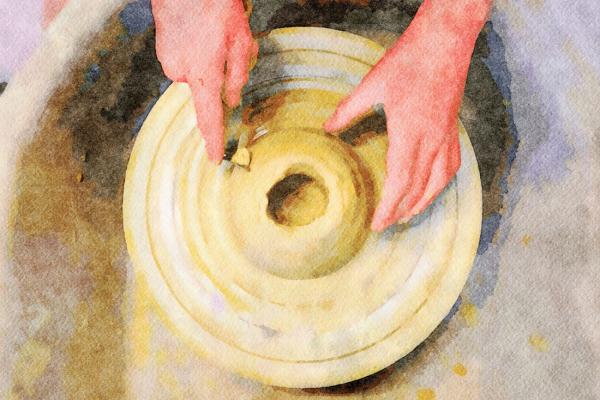

“CENTER THE CLAY.” I had one task for class and three hours to complete it.

Take two pounds of raw potential. Place it on the potter’s wheel. Use the strength of your hands and forearms to force the clay into balance.

For the full three hours, I failed. Unable to find the calm point of pressure to rest my human musculature between the universe’s centrifugal and centripetal forces. The clay fought back. It bucked and shimmied, slid and skidded. I pushed and pulled.

The teacher said, finally, “This clay does not yet want to be a bowl. You have not shown it how.” A gentle correction that expertly undermined my fixation with “the primacy of the real,” as French philosopher Gaston Bachelard calls it. Really, shouldn’t I be able to subdue this clay?

Read the Full Article