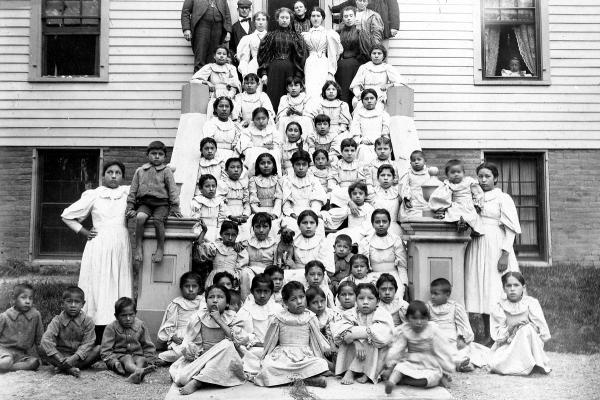

WHEN POPE FRANCIS visited Canada in July 2022, he said he was “deeply sorry” for the abuses inflicted upon peoples from First Nations by more than a century of Catholic-run residential schools. Francis decried the ways “many Christians supported the colonizing mentality of the powers that oppressed the Indigenous peoples,” which resulted in “cultural destruction and forced assimilation.”

To his credit, the pontiff acknowledged that his apology was not “the end of the matter,” and that serious investigation of what was perpetrated and enabled by the church was necessary for the survivors of the schools “to experience healing from the traumas they suffered.”

In the United States, the Seneca Nation is paving a path toward that healing process in their homelands, in particular from harm caused by a Presbyterian-run residential school.

A month after the pope’s apology, Matthew Pagels, then-president of the Seneca Nation — which historically inhabited territory throughout the Finger Lakes and Genesee Valley regions of New York — announced a new initiative to compile and catalog a list of residential school attendees.

To lead the effort, Pagels tapped Sharon Francis, a member of the Wolf Clan of the Seneca Nation and program coordinator at the Seneca Nation crime victims unit. Her passion, she said, is helping her communities heal from personal, intergenerational, and historical traumas.

Read the Full Article