Figuring out why Pope Francis has upended so many expectations, how exactly he’s changed the Catholic Church in his first year and what he might be contemplating for the future has become a Catholic parlor game that is almost as popular as the pontiff himself.

A single key can best answer all of these questions: Francis’ longstanding identity as a Jesuit priest.

It’s an all-encompassing personal and professional definition that the former Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio brought with him from Buenos Aires, and one that continues to shape almost everything he does as Pope Francis.

“He may act like a Franciscan but he thinks like a Jesuit,” quipped the Rev. Thomas Reese, a fellow Jesuit who is a columnist for National Catholic Reporter.

Walls exist between U.S. and Mexico. A few years ago, I took a class to the Mexico-U.S. border through BorderLinks, an organization that provides educational experiences to connect divided communities, raise awareness about border and immigration policies and their impact, and inspires people to act for social transformation. We visited the metal wall that separates the United States from Mexico at Nogales, Mexico.

The walls went up in 1994.

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), established in 1994, was supposed to help with trade and the economic status of Mexico. However, it failed to do this. It backfired and made the economic situation worse for the people of Mexico. Rich corporations and companies that benefited from the Free Trade Agreement as they were able to move their factories down to Mexico where the labor was cheap and profits higher. As the economy of Mexico suffered, more people made their way, without documents, to the United States to seek work so they could support their families.

In 2006, the United States responded with the Secure Fence Act. As President George W. Bush signed the bill, he stated, “This bill will help protect the American people. This bill will make our borders more secure. It is an important step toward immigration reform.” The act included provisions for the construction of physical barriers — walls — and the use of technology to these ends.

This wall is under constant surveillance to prevent people from entering into the U.S. illegally. Ironically, it is a wall built from the remaining metal landing scraps of the Gulf War. The border is highly militarized with patrols who treat migrants as “prisoners of war.” It symbolizes militarization, greed, xenophobia, hatred, pride, nonsense, and fear of the other, a reminder of wanting to protect what is yours and not sharing what God has given you. Walls continue to go up along the border as the people of the United States continue to fear that undocumented people will take away jobs. These fears may devastate the lives of the poor in both countries.

As the number of Muslims in Bangui, the Central African Republic capital, dwindles to an estimated 900, the head of a global alliance of churches has urged tackling the conflict from a political rather than a religious angle if the Muslim exodus is to be reversed.

The alliance is one of the agencies providing humanitarian assistance in the country, where chaos erupted last year after the mainly Muslim rebels toppled the government.

The Seleka rebels looted, raped, and killed mainly Christian civilians, prompting the formation of an equally brutal pro-Christian anti-Balaka (anti-machete) militia.

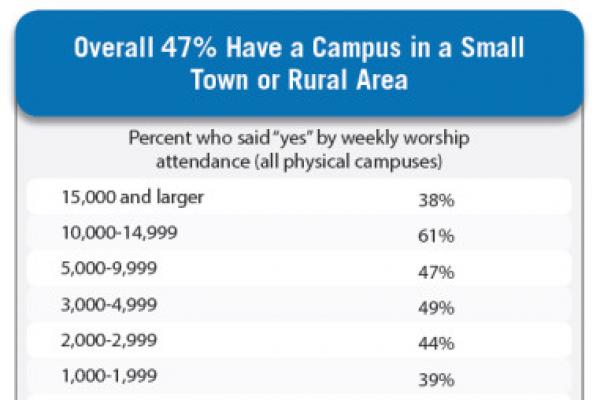

The vast majority of multisite churches are growing, according to a new study, and they are seeing more involvement from lay people and newcomers after they open an additional location.

Nearly one in 10 U.S. Protestants attends a congregation with multiple campuses, according to findings released Tuesday in the “Leadership Network/Generis Multisite Church Scorecard.”

The report cites new data from the National Congregations Study, which found there were 8,000 multisite churches in the U.S. in 2012 — up from 5,000 in 2010 — including churches with more than one gathering on the same campus. Churches that have created worship space in a separate setting now exist in almost every state, several Canadian provinces, and dozens of other countries.

Multisite churches typically operate with a main campus headed by the senior minister and one or more satellite locations. In some settings, attendees at the satellite location watch the same sermon that’s beamed in from the central location but have their own dedicated on-site pastor, music, or small group meetings.

I’ll just say it: I thought “ashes to go” was a great idea.

Thousands of clergy and lay liturgists did “to-go” this year. From all evidence, it was a great hit.

Not everyone appreciated the innovation, of course. But then not every Christian appreciates a liberation-minded pope, or songs on projection screens, or preachers in jeans, or services at any time other than Sunday morning, or ditching denominational hymnals, or coffeehouses doubling as worship venues.

Prison guards meet in the desert to hand off chemicals for executions. A corrections boss loaded with cash travels to a pharmacy in another state to buy lethal sedatives. States across the country refuse to identify the drugs they use to put the condemned to death.

This is the curious state of capital punishment in America today.

At the same time, growing numbers of states are ending capital punishment altogether. Others are delaying executions until they have a better understanding of what chemicals work best. And the media report blow-by-blow details of prisoners gasping, snorting, or crying out during improvised lethal injection, taking seemingly forever to die.

Legal challenges across this new capital punishment landscape are flooding courts, further complicating efforts by states that want to keep putting people to death.

Cardinal Timothy Dolan said Sunday that Pope Francis is asking the Catholic Church to look at the possibility of recognizing civil unions for gay couples, although the archbishop of New York said that he would be “uncomfortable” if the church embraced that position.

Francis said the churches in various countries must account for those reasons when formulating public policy positions. “We must consider different cases and evaluate each particular case,” he said.

When facing a crisis, silence is certainly easiest. But silence isn’t best. As we face some very challenging environmental issues, evangelicals must learn to begin to discuss the environmental crisis with creativity and integrity. Whether it’s because we know we play an integral role in the healing of the world, in agreement with Wendell Berry, who says our fate is “mingled in the fate of the world.” Or, because we’ve come to see our responsibility to care for God’s creation as a central aspect of our love of Jesus Christ. Regardless of our reason — silence can’t be our policy.

In a very real sense, the easiest way for us to deal with the realities of the 21st century ecological crisis is practicing a kind of mutual pretense. That’s the easiest thing to do. Despite the humming knowledge that hard things await, we will talk about anything without actually talking about what is going on. More than many, I know that this can be the practice of evangelical Christianity in which I am rooted. We’ll talk about the return of Jesus, about theology, about church practice, anything but what’s actually going on in our world.

To my mind, all of Wes Anderson’s films are masterpieces in the truest sense of that word. But his most recent creation, Grand Budapest Hotel, is, perhaps, his chef d’oeuvre.

Anderson’s eighth feature-length film, which opened in limited release last week, Grand Budapest Hotel is a whimsical, hilarious, and surprisingly touching tale laden with nostalgia for a world and way of life most of us (including the 44-year-old director himself) never have experienced.

Set in the fictional Eastern European mountain region known as the “Republic of Zubrowka,” the plot centers around the character and adventures of Monsieur Gustave H. (Ralph Fiennes), the concierge of the eponymous Grand Budapest Hotel, one of Europe’s palatial “grand hotels. Gustave is something of a dandy, a throwback to a bygone era even in his heyday of the 1930s on the cusp of World War II.

)