Amid calls for a Vatican investigation, Newark Archbishop John J. Myers is facing fierce criticism for his handling of a priest who attended youth retreats and heard confessions from minors in defiance of a court-ordered lifetime ban on ministry to children.

At St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Colts Neck, where the Rev. Michael Fugee had been spending time with a youth group, angry parishioners said they were never told about Fugee’s background, and they questioned Myers’ defense of the priest, the subject of a lengthy story in The Star-Ledger.

“It’s complete craziness that the church can let this happen,” said John Santulli, 38, a father of two at St. Mary’s. “I’m a softball coach, and I need a background check just to get on the field. Every single person I spoke to today said, ‘Oh my God. I didn’t know about this.’ It’s incomprehensible.”

If Congress passes immigration reform, much of the credit will be given to the broad and diverse voices that have lined up in support of fixing our nation’s broken immigration system. Both the labor and business community have been instrumental in moving legislation forward, while the evangelical community’s call to “welcome the stranger” has received significant attention by politicians and the media. The coalition of supporters continues to grow, as last week the Sierra Club, the oldest environmental organization in the country, announced its support for immigration reform.

Why would an environmental organization get involved with immigration reform? What could they possibly have at stake?

A lot.

Editor’s Note: Jim Wallis’ latest book On God’s Side: What Religion Forgets and Politics Hasn’t Learned About Serving the Common Good is sparking a national conversation of what it means to come together on issues that traditionally divide the nation. Bloggers Adam Ericksen and Tripp Hudgins are having that conversation here, on the God’s Politics blog. Follow along, and join the discussion in the comments section.

In his post “Lattes for the Common Good,” Tripp states that working for the common good starts in mundane places, like a coffee shop. These are the places where we practice neighborliness. Here’s Tripp’s brilliant point:

I wonder if one of the things that we can think about in terms of the common good is learning to practice neighborliness in the inconsequential moments so that when we face the bigger political difficulties of our shared life — when we start talking about the common good in the larger sense around some of the other issues like violence, and fear, and money — that maybe if we've already built up habits we can have these larger conversations with greater ease.

Jim Wallis says something very similar in his book On God’s Side. When it comes to the common good, Wallis states, “I have never seen the real changes we need come from inside politics. Instead, they come from outside social movements” (295).

According to Wallis, for those social movements to make any real change in our politics they must be based on the biblical command to “love your neighbor as yourself.” Indeed, On God’s Side begins with a reflection on the Golden Rule. And, as Tripp says, “learning to practice neighborliness” is learning to practice loving our neighbor as we love ourselves.

But there is a tension in Wallis’s book that, for me, is unresolved. That tension is clearly seen when Wallis talks about baseball.

JERUSALEM — Religious leaders from around the world have stepped up their pleas for the safe return of two Syrian bishops who were kidnapped April 22 by armed men as they were driving near the war-torn city of Aleppo.

The kidnappers, who have not been identified, abducted Greek Orthodox Metropolitan Boulos Yazigi and Syriac Orthodox Metropolitan Youhanna Ibrahim, both of Aleppo, while they were undertaking a “humanitarian mission” to help Syria’s Christian minority, according to Syrian Christian expatriates in the U.S.

The bishops’ Syrian Orthodox driver was killed in the attack.

Since 2011, more than 70,000 Syrians have died in fighting in the bloody civil war between forces loyal to Syrian President Bashar Assad and rebels seeking to oust Assad’s strong-arm regime.

In today’s White House press conference, CBS News' Bill Plante raised the questions with President Barack Obama about the growing hunger strike among prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. “Is it any surprise, really,” asked Plante, “that they would prefer death rather than have no end in sight to their confinement?"

"Well, it is not a surprise to me, “ President Obama responded, “that we've got problems in Guantanamo.”

Last week, a military spokesperson confirmed that the total number of irregularly held prisoners at the U.S. Naval prison at Guantanamo Bay has risen to 92 out of the 166 still in detention.

The Guantanamo prisoners began hunger striking on Feb. 6 after guards confiscated their Korans to examine them for contraband. The prisoners reported that their Korans had been desecrated by the guards, which a military spokesperson denies. Fueling the strike is the men’s loss of hope of ever leaving Guantanamo alive, most having been held more than 11 years without charge and Obama refusing to free even the 86 cleared for release.

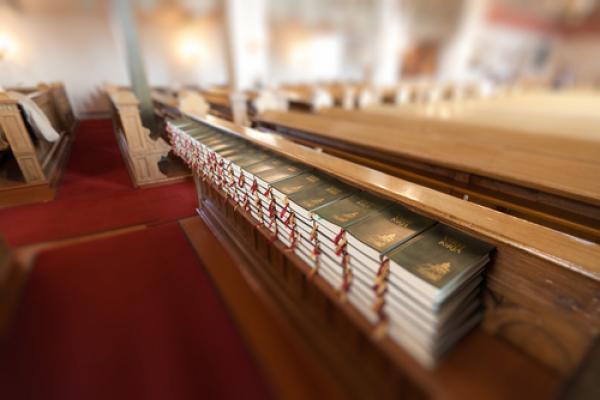

Most songwriters in Nashville want to get their songs on the radio. Keith and Kristyn Getty hope their songs end up in dusty old hymnbooks.

The Gettys, originally from Belfast, Ireland, hope to revive the art of hymn writing at a time when the most popular new church songs are written for rock bands rather than choirs.

They’ve had surprising success.

One of the first songs that Keith co-wrote, called “In Christ Alone,” has been among the top 20 songs sung in newer churches in the United States for the past five years, according to Christian Copyright Licensing International. It is also a favorite in more traditional venues — including the recent enthronement service for Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby.

Hearing that hymn sung by a boys’ choir with a brass ensemble and thousands of worshippers was a thrill for Keith Getty, a self-described classical nerd.

Five men who know what it means to be president of the United States shared a stage in University Park, Texas. Then the incumbent among them flew to Waco, to mourn 11 first-responders, killed in a fertilizer plant explosion in the small town of West, Texas.

All presidents try to rewrite history to burnish their brief place in it. And in his new presidential library, George W. Bush will have his turn.

Barack Obama’s legacy is still a work in progress, though even sympathetic commentators are seeing him now, in his fifth year, as too slow to act, too cerebral to brawl, and too little respected by his political enemies.

In one role, however, Obama has excelled: “Mourner in Chief” — not one of his constitutional duties but oddly important.