The Ecclesial Network for the Amazon, a Catholic church network representing 12 Latin American countries, met recently in Puyo, Pastaza, Ecuador, challenging unrestrained market forces that are decimating the Amazonian ecosystem. The Network has been established to provide on-the-ground facts about Amazonia's environment, indigenous communities, and to strengthen the church in the region. Agenzia Fides reports:

"Many people still think that there is an unlimited amount of energy and resources that can be used, and that the negative effects of the wild manipulation of nature can be easily absorbed. But this is totally false." Such attitudes, Catholic Bishop Julio Parrilla continued, "are not rooted in science or technology, but in a technocratic ideology that serves the interests of the market." The Bishop concluded by reiterating "the influence of secularization, because when man turns away from God, he falls into the temptation of thinking that everything is permitted, in order to meet one’s immediate needs and desires."

Pastor Greg Laurie knows a thing or two about prayer in tough times.

The honorary chairman of this year’s National Day of Prayer (May 2) says prayer was the only thing that got him through his son’s death five years ago. When fellow megachurch pastor Rick Warren lost his son Matthew to suicide, Laurie was the man he most wanted to hear from.

Laurie, 60, who leads the evangelical Harvest Christian Fellowship in Riverside, Calif., talked about prayer, grief, and what not to say when a friend’s loved one dies. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

WASHINGTON — The adult survivors of the Holocaust are mostly gone now, and those who survived as children — and were old enough at the time to remember their ordeals — are now in their 70s and 80s.

It won’t be long before no eyewitnesses remain.

That’s why, as the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum marks its 20th anniversary today (April 29) with more than 750 survivors, museum officials are calling it one the last large gatherings of those who managed to escape Hitler’s death machine.

For those who have dedicated themselves to teaching future generations about the Holocaust and its victims, the demise of the survivors means looking backward in a different way — a way that no longer includes people looking others straight in the face and recounting what they saw and what they lived.

I’ve experienced some strange extremes lately. First, I attended – and spoke at – the Subverting the Norm conference in Springfield, Mo., where we took some time to consider how, if at all, so-called “radical theology” could exist within today’s religious systems. Then I got home and found my latest TIME Magazine, with a cover story titled “The Latino Reformation,” which reveals what most within Protestantism have known for some time: formerly Catholic Latino Christians are dramatically reshaping the face of the American Christian landscape.

Interestingly, there is little-to-no overlap between these two groups – a point which was made clear to me by the fact that there were very few people of color in attendance at Subverting the Norm. One comment, from an African-American woman who was there, was that the very focus of the conference (on academic, esoteric questions of theology and philosophy) assumed the kind of privilege still dominated by middle-class white males. Put another way: while we’re busy navel-gazing and discussing the meaning of Nietzsche’s “death of God,” non-Anglo religious leaders were busy dealing with real-world problems right in front of them.

Most Americans sat glued to the TV or radio on April 15 (or raced to finish tax returns) transfixed by the horrific Boston Marathon bombing and aftermath. Nearly 100 friends of Fr. Michael Lapsley’s gathered that evening at Busboys and Poets restaurant and bookstore in Washington, D.C., to be soothed with a testimony of faith by South African Ambassador Ebrahim Rasool, soul-stirring cello music, and a transporting testimony of healing by apartheid regime bomb victim “Father Mike.”

One of my favorite newspapers in the world, the South African Mail and Guardian, reported on April 19 this way:

“Boston bombings: the marathon struggle of survival and healing … a priest from South Africa, apartheid fighter and a bomb victim himself reaches out to Americans about forgiveness … He had not planned it that way. The event was to launch his book. It had been scheduled for last October but Hurricane Sandy scuppered those plans. Instead it took place on a day when three people were killed and more than 100 injured in Boston.”

Paranorman, the stop-motion animated feature by Laika Studios just came out on Netflix instant download, so we decided to watch it for our family movie night. It's a fun film, perhaps a bit too scary for the little ones, but what really stood out for me was the surprisingly deep morality in this little film. This comes in an unlikely package since the film is about zombies and witches. Not surprisingly, if you look for Christian reviews of the film you will see many focus on warnings to stay way from the occult. Sadly, this response misses the profoundly deep moral message behind this film — one that confronts religious violence, and instead promotes a message of redemption and forgiveness. That's quite a bit of insight for a cartoon!

The premise of Paranorman is that the town of Blithe Hollow (not coincidentally set in Massachusetts, as we will see later) is about to be overrun by zombies because of the curse of an evil witch. Only Norman Babcock, an odd boy who can speak to the dead, can save the day. The movie begins by having us get to know Norman, who is emotionally isolated because his family does not understand him, and his peers ostracize and ridicule him as a "freak" at school. The only person who believes Norman is his friend Neil Downe, and overweight boy who is himself bullied.

The town is in peril because three centuries ago, an evil witch was executed, and in revenge put a curse on puritan judge and her accusers, cursing them to rise from the grave as zombies. So each year the curse of the witch must be appeased by reading from a mysterious book at the grave of the witch in order to prevent a zombie apocalypse. But this year that does not happen, and the zombies overrun the town. The townspeople and local police form the typical Frankenstein mob, complete with pitchforks and shotguns to kill the zombies. As the mob mentality grows, Norman and his motley band are threatened by the mob as well.

This is the first point where we see the film’s unmasking of "virtuous" violence: in the logic of many films, so long as someone is a "monster" or an "alien," it is okay to kill them. So we have no problem with watching mass killings of monsters or aliens in movies because ... well ... they're monsters. So you're supposed to kill them. That's what good guys do in movies. This is the unquestioned plot of hundreds of movies. As long as the Storm Troopers in Star Wars are faceless, we don't bat an eye when Luke kills one after the other. They have been dehumanized, and so it's okay to kill them all. The same is true for the Orks in Lord of the Rings, or the witch and her minions in the Chronicles of Narnia.

By definition, an anesthetic is a drug used to relieve pain (analgesia), relax (sedate), induce sleepiness (hypnosis), spark forgetfulness (amnesia), or to make one unconscious for general anesthesia. Anesthetics are generally administered to induce or maintain a state of anesthesia and facilitate a procedure. I believe that anesthetic can be employed as a striking image for particular deficiencies in faith-based responses to extreme poverty.

As one can cite many examples where faith is proclaimed and practiced solely as an escape from – rather than engagement with – the numerous struggles associated with impoverishment, we recognize that anesthesia is incomplete without corresponding acts of sustainable social surgery.

...

A practical way to serve within the tension of anesthetic and advocate is to experience a small portion of life below the poverty line. The World Bank sets extreme poverty as below $1.50 per day, and I plan to stand in solidarity by attempting to eat on less than $1.50 per day over the course of five days (Monday – Friday).

Over the last several weeks, I’ve been trying to figure out exactly why I feel so bothered by Sheryl Sandberg’s book, Lean In.

I suggested to my husband that maybe I’m being defensive since I am an educated woman in a professional field who has very clearly chosen to “lean out” to spend more time at home.

Or maybe it’s because I disagree with putting any degree of blame for inequality in the workforce on women.

Or maybe it’s because I don’t like the idea of human capital.

None of those reasons, however, seem to explain why the book and the phrase “lean in” have become such an obsession for me. I certainly consider myself a huge proponent of equality and women’s rights. I have marched, protested, researched, worked toward, and fought for true equality for women all of my adult life.

So my discomfort with Sandberg’s book isn’t because I’m anti-woman or anti-feminist. It isn’t because I disagree with her and want all moms to stay home and bake cookies and volunteer for PTA. It isn’t even because I feel the need to defend my choice to be a 99-percent stay-at-home mom. Instead, it’s because, as a Christian, I believe that the whole idea of “leaning in” does not take into account the principle of putting others before self. (Phil. 2:3-8). This principle applies equally to both women and men.

(Caveat: neither women nor men should be trapped into subservience by children and/or spouse. I am talking about putting the real, rational, and loving needs presented by being part of a family before one’s individual needs.)

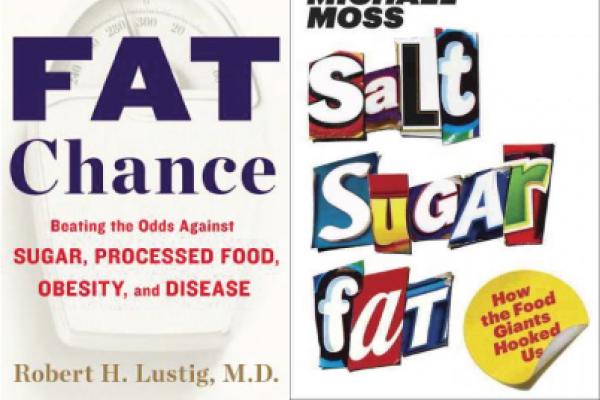

If you eat food, here are two newish books you should know about.

You may already have met Robert H. Lustig, author of Fat Chance: Beating the Odds Against Sugar, Processed Food, Obesity, and Disease (2012). Lustig is the UCSF professor whose surprisingly riveting 90-minute lecture, "Sugar: The Bitter Truth," has already had nearly 3.5 million hits on YouTube. The thesis of his lecture: it's not dietary fat that's making Americans gain weight, it's sugar. And sugar is doing much worse things than increasing our clothing size. It's setting us up for a whole range of lethal diseases that are almost entirely avoidable.

...

In Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us (2013), Moss, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter, tells what the food industry has been up to during the last couple of decades. Food executives, Moss says, are nervous: people are figuring out that convenience foods aren't good for them.