Eric Garner

IN 2018, CLIMATE SCIENTISTS reached a consensus that, based on current global emissions, we have roughly 12 years to dramatically reverse course before we cause irreparable harm to our planet and our way of life. These and other predictions cause me to lose sleep at night, particularly when I think about the world that my two sons will inherit.

But this alarming trend is not inevitable, nor are we powerless to change course. Preventing the worst consequences and putting the planet on a zero-carbon trajectory will require a revolution of social and political will. Catalyzing this revolution will require new language, new metaphors, and new messengers.

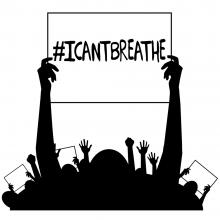

“I can’t breathe.” These were the prophetic words said by my pastor, Rev. Howard John-Wesley, in a sermon in which he made the case that we are on the brink of ecological destruction. He preached about the thousands of species that go extinct every year. He emphasized that Americans constitute 5 percent of the world’s population but burn 25 percent of the world’s fossil fuels. These and other trends of conspicuous consumption and abuse are driving us toward global catastrophe.

The police department plans to stop honoring those requests and bring proceedings against officers involved in Garner's death on Sept. 1 if there has been no federal prosecution decision announced by then, Byrne wrote.

Image via Rena Schild/ Shutterstock

What we’ve learned three years after Eric Garner’s death is that we can’t give up on God’s mandate for justice, incarnated in the gospel’s good news. If we trust and believe that selfish agendas of special interests will not prevail, we are compelled instead to believe that love will conquer hate.

Image via a katz/Shutterstock.com

The Injustice Boycott has selected three locations that it plans to affect: New York City, San Francisco, and Standing Rock. The initiative will give the government leaders of those locations until Jan. 17, the day after Martin Luther King Jr. Day, to answer to the demands of local activists and organizers, and if those demands aren’t answered by that day, the Injustice Boycott will launch several actions against the city. These actions will include a tourism boycott of those cities; pulling money out of banks, financial institutions, and large corporations that either support racial injustice and police brutality in those cities or have not come out against them; and protests in the city that will be designed to shut down the work of businesses and city government.

An interview with author Lisa Sharon Harper.

The hospital that dispatched paramedics to treat Eric Garner, who died after being placed in a police chokehold, has agreed to pay his family $1 million. Video of Garner’s arrest shows an officer putting him in a chokehold as Garner yells, “I can’t breathe!” which became a protest slogan for the Black Lives Matter movement. When emergency responders from Richmond University Medical Center arrived, they did not perform CPR.

August 2104 rally to address the ongoing violence in Ferguson, Mo., attended by Congressman Hakeem Jeffries & the Garner family. a katz / Shutterstock.com

7 Our ancestors sinned the great sin of instituting slavery; they are no more—but we bear their shame.

8 The system of slavery and institutionalized racism ruled over us,

and there is no one to free us from their hands.

9 We get our bread at the risk of our lives because of the guns on the streets.

Please don’t fail to recognize this vital moment in American history: when our fellow citizens screamed for equality, marched for recognition, and pleaded for justice. Because someday the next generation will ask us: What did you do?

And so today we must ask ourselves: What are we doing? What are we seeing? What does this all mean?

Because the last few years within our country — a continuation of the past hundreds of years — have been socially jarring for a society that considers itself a modernized, technologically advanced, and morally superior nation

1. ‘A Rape on Campus:’ What Went Wrong?

Columbia University’s Journalism school released its report detailing the journalistic failures of Rolling Stone’s viral story ‘A Rape on Campus,’ which initiated, and later may have stifled, an honest conversation about the prevalence rape on college campuses. Read the full report. “[Writer Sabrina Rubin] Erdely and her editors had hoped their investigation would sound an alarm about campus sexual assault and would challenge Virginia and other universities to do better. Instead, the magazine's failure may have spread the idea that many women invent rape allegations.”

2. The Courage of Bystanders Who Press ‘Record’

“Despite the fact that the world can now see Eric Garner being killed by an illegal chokehold — despite the fact that New York City Police Department banned chokeholds years ago — film of the incident did not result in the officer, Daniel Pantaleo, being charged. But thanks to the efforts of Ramsey Orta, who filmed Garner’s death, we know.”

3. Hope but Verify: The Iran Nuclear Framework

“House Speaker John Boehner recently said this about the broader instability in the Middle East: 'The world is starving for American leadership. But America has an anti-war president.' In the context of our faith — or even in the context of conservative ideals — is leadership that prevents war something to be maligned?”

4. How the Presidential Candidates Found Their Faith

“This season’s crop of presidential candidates reflects this country’s many contradictions in faith.” Newsweek explores the faith backgrounds of the apparent 2016 field so far.

It is difficult to understand why people, particularly Christians, view a statement as patently obvious as “Black Lives Matter” as a subject for controversy. However, sometimes the most obvious things still need to be said.

So:

Black lives matter because God made every one of us in God’s image. Black lives matter because the Bible tells us that we are part of a body and the eye cannot say to the hand, “I don’t need you.” Black lives matter because God pays particular care to those crying out under the burden of injustice and oppression.

As people of faith in a neighborhood that has been rocked by protests, tear gas, and arrests, we have sought to stand in solidarity with those who are groaning under the burden of oppression. We offer some physical support — hand warmers, a cup of coffee, an extra pair of socks, but we also offer our presence. The Bible often refers to Christians as “witnesses,” and there is something important about simply standing next to our neighbors in the streets and seeing what is actually happening.

We firmly believe that Jesus needs to be down in the clouds of tear gas and he lets us, his people, participate in his reconciliation by bringing him there with our own two feet. Christians, and particularly evangelicals, need to be in the streets. Our neighbors are just outside our doors, crying out that the system is broken and that our culture doesn’t value the lives of our brothers and sisters. We, as Christians, believe in sin and brokenness and we need to live out our belief that God values all of God’s people even as our culture picks and chooses who is worth caring about.

Maybe I am the only one wondering “What can I do?” as I watch and read the news of demonstrations throughout the country. I have a lot of excuses. I can’t go to the protests tonight because my son has a concert. I don’t coordinate the church service and announcements, so I can’t control what will and won’t be said. I’m on sabbatical so I won’t be a part of the conversations that I hope will happen between colleagues at meetings. But I hope I am not the only one wondering what can be, needs to be, ought to be done.

The videos are chilling – Eric Garner’s life is being choked out of him until he goes limp on the sidewalk and Tamir Rice is being gunned down, the police squad door barely opening as the officer drives by. The images of protests and protesters being tear gassed and throwing canisters back at police armed in riot gear remind me of the summer I spent in Korea, marching in protests against U.S. military presence. That was the summer I learned about wearing damp handkerchiefs near my eyes and over my nose to help with the sting of tear gas and how to wet the wick of a homemade Molotov cocktail before lighting and lobbing. A few years later in a hotel room in Indiana after a job interview, I watched protests and riots take over Los Angeles. Living with, wrestling with injustice day in and day out is a bit like a kettle of water just about to hit boiling. At some point, the water boils, the steam is released.

What can local churches do to support ongoing protests against, and indeed upheaval of, an unjust criminal justice system and deep-seated white supremacy? In a season that Lisa Sharon Harper recently described as “Advent as protest,” what might it mean for Christians to anticipate the coming of Christ by physically challenging oppression? For pastors all over the United States, these are the questions of the moment.

In Washington, D.C., local faith communities sought to live into the vision of Advent as protest by holding a “vigil for justice.” Although this vigil beautifully documented the capacity of the local church to advocate for justice, the way local media framed the vigil forces communities of faith to think more deeply about their understanding of solidarity.

Spread out along nearly 6.5 miles of 16th Street, hundreds of people held candles and signs in support of recent protests against racial injustice. As people passionately waved their signs or held their heads down in prayerful lament, passing cars and buses slowed to honk in support. Catching on with the theme of Advent, attendees hoped to shine light in the darkness not only to create awareness and show solidarity, but also to testify to the hope of faith.

Cecilia Choi, a member of District Church explained, “This is the time of Advent when God came and he started his work of reconciliation with us by becoming one of us. And I think it’s perfect to come out and work on reconciliation and joining with our black brothers and sisters. They’re not just our neighbors, they’re our brothers and sisters in Christ. We have such an obligation to them. I think this is an act of worship.”

When asked why she was on the streets, one woman responded, “Well, what do I say? [Laughs.] That’s the meaning of our faith! To be one with people who are suffering.” Another man called racism “the deepest sin in the United States.”

Such descriptions of the vigil reach to the core of the church’s mission to “do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly.” Here are churches standing in solidarity with those suffering at the hands of racist oppression as an “act of worship.” Here are churches bringing their resources of prayer, lament, and peace into the public sphere, challenging observers to wrestle with God’s call to justice. Yet, though the event was beautiful, the way it was framed by local media raises tough questions for churches. Contrasting this demonstration with other recent protests, one reporter said, “This protest was in contrast to many of the protests we’ve seen over the past few weeks, with groups blocking traffic and loudly chanting. This group was quiet and purposeful.”

“Excuse my ignorance, I thought I was a free black man.”

“I’m 11 [years old], I matter.”

“You can choose to look away, but never again can you say you didn’t know.”

“How many times do we have to protest the same [s**t]?”

“White silence is white violence.”

“We have nothing to lose but our chains.”

These signs, and many others, lined the horizon of Pennsylvania Avenue on Saturday in Washington, D.C. In a ‘Justice for All’ march organized by Al Sharpton and the National Action Network, thousands of protesters gathered to protest police actions that have resulted in the deaths of unarmed young black men across the United States.

After marching from Freedom Plaza to the U.S. Capitol, protesters listened to speakers from national racial justice organizations address some of these most recent acts of police brutality.

Al Sharpton sought to draw attention to the diversity present on the streets.

“This is not a black march or a white march. This is an American march for American rights,” he said.

Indeed, the black community was not alone in speaking up against police brutality. One Latina activist encouraged her Latino brothers and sisters to “voice their pain” from police harassment and “come forth and unify with the African American community so we can be strong together.”

“¡Ya Basta!” she concluded. [“Enough is enough!”]

The stories of young black men being killed by white police are sparking a national conversation. However, public responses to these painful stories reveal an alarming racial divide. From an unarmed teenager killed in Ferguson, Mo.; to a 12 year-old boy shot dead in Cleveland; to a white police officer on video choking a black man to death in New York City; and a startling series of similar stories from across the country and over many decades — our reactions show great differences in white and black perspectives.

Many white Americans tend to see this problem as unfortunate incidents based on individual circumstances. Black Americans see a system in which their black lives matter less than white lives. That is a fundamental difference of experience between white and black Americans, between black and white parents, even between white and black Christians. The question is: Are we white people going to listen or not?

White Americans talk about how hard and dangerous police work is — that most cops are good and are to be trusted. Black Americans agree that police work is dangerously hard, but also have experienced systemic police abuse of their families. All black people, especially black men, have their own stories. Since there are so many stories, are these really just isolated incidents? We literally have two criminal justice systems in America — one for whites and one for blacks.

Are there police uses of force that are understandable and justifiable? Of course there are. If our society wasn’t steeped in a gun culture, many of these shootings could be avoided. But has excessive, unnecessary, lethal force been used over and over again, all across the country, with white police killing unarmed black civilians? Yes it has, and the evidence is overwhelming. But will we white people listen to it?

At the point of the writing of this article, it has been 124 days since unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown was shot six times and killed by Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson.

Blocks from the spot where Brown lay dead in the tightknit Canfield neighborhood of Ferguson, Mo., protestors filled West Florissant Avenue, where Brown had been only minutes before his death. They were met by the local police force decked out in camouflage and body armor, armed to the gills with military-grade weapons, and rolling around in armored cars. Many commented that the streets of Ferguson looked like Fallujah.

It was both shocking and clarifying at once.

For the first time, Americans witnessed real-time outcomes of the National Defense Authorization Act, which funnels military weapons left over from past wars to local police municipalities across the country — in theory, to fortify local efforts in America’s drug war. Cable news cameras swarmed as wartime weapons, tactics, and protocols were enacted on unarmed, mostly black citizens exercising their First Amendment rights to assemble and exercise free speech.

Here’s the thing about war: There are only enemies and allies. There is no in-between.

Our nation stands at a crossroads moment as the simmering crisis around policing and our justice system reaches a boiling point. Recent cases of police violence in Ferguson, Cleveland, and now Staten Island have stirred an awakening around what is increasingly understood as a pervasive and pernicious problem in America in which black lives are too often treated differently when it comes to police accountability and criminal justice.

Last week, I had the privilege of participating in a retreat with other faith leaders convened by Sojourners to learn about and make common cause with the ongoing efforts to seek justice in the tragic death of Michael Brown Jr. We spent a day talking to local faith leaders and young activists. We visited the memorial site in Ferguson where Brown was tragically killed and the streets where 120-plus days of protest have ensued. While it was heart-wrenching to stand and pray at the site where Brown was killed, I left the two days filled with a resilient sense of hope based on our conversations and interactions with a cross section of young people, most in their early to mid-20s, who embody modern-day freedom fighters. I hope we as a nation can listen to their voices and come to know their stories as we seek answers around what our response should be.

Young activists at the center of the protest movement in Ferguson are refusing to accept cosmetic change or symbolic commitments; instead they are fighting to transform their community and our nation so that neither punishment nor privilege will be systemically or viciously tied to the color of our skin. In the process, these young activists are picking up the broken pieces of the civil rights struggle. Their courage, willingness to sacrifice, and bold vision gave me a great deal of hope for what America can be.