Advent

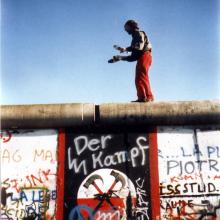

The wall wasn’t supposed to come down.

Günter Schabowski, a spokesperson for the East German Politburo, was tired. He hadn’t thoroughly read the travel regulation updates, handed to him shortly before his news conference. He didn’t know the document’s shifts in rhetoric, developed by leaders in the East German government, were simply an attempt to appease the swelling ranks of East Germans demanding reform. On Nov. 9, 1989, facing journalists’ cameras and notepads, Schabowski took questions for a forgettable almost-hour. Then someone asked about rumors the border may open.

Schabowski mumbled over his answer, confused. But a few of his words were clear: “Immediately ... right away.”

Reporters pounced. Breathless reports in West German media soon filtered over the wall through East Germans’ pirated signals. The Politburo had assured checkpoint guards that no changes had been made, but it was too late—a trickle of curious East Berliners quickly grew to massive crowds, yelling “Open the gate!” At a loss, and unable to get through to leadership for clarification or backup, the guards eventually gave in. Within hours, nearly 40 years of iron-fisted East-West divide was undone.

One of the most familiar biblical passages to be read during Advent is from Isaiah 9:6: “For to us a child is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders. And he will be called Wonderful Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.”

At the time it was spoken, the whole world was falling apart, or so it seemed to the eighth-century prophet Isaiah. Looking over history at a string of failed rulers, and staring into the abyss at ongoing chaos and political disaster, Isaiah looked forward to a time when God would send an heir to the throne who would be a different kind of ruler, a divinely appointed one (the Messiah), and his name would tell his character. Isaiah promised a people whose hope was failing that a baby would be born.

But where do babies come from? They come from women, women who endure the discomforts of pregnancy and the excruciating pain of labor to bring forth life.

In January 2016, the Rev. Cynthia Meyer told her United Methodist Church congregation she felt “called by God to be open and honest” about who she is: “a woman who loves, and shares her life with, another woman.”

On Jan. 21, I’ll join thousands in D.C. for the Women’s March on Washington. My first stop will be at a local congregation, one of several hosting a prayer service and warming station for marchers. I’m an anti-racist, feminist, Christian, and for me, faith will be part of the day.

I’ve been disappointed with Christian silence, and even active resistance, to social justice imperatives, but my commitments to justice stem from my faith, and that’s why I march.

If irony wasn’t dead, I’d say how ironic it was that in the midst of this season of Advent, in which we look to the nebulous future, a time-not-yet shaped by our ability to be patient and hopeful and tense and a bit sorrowful about what we cannot see but hope we shall soon see, our societal life is filled with those for whom there is no future.

This sight of poor refugee parents and a humbly born baby surrounded by dirty shepherds and visitors from other religions and races and cultures should jolt us. It’s meant to. The manger shows us a world far different than our own, one that we’re being summoned to create with unconditional love and inclusion.

When we talk about the Advent season, we use the language of longing. But rarely do we speak about the chaos and glorious disruption that follows when this holy Love arrives.

1. A White Supremacist By Any Other Name

“… it quite literally took [Richard] Spencer and other members of the alt-right ending a meeting with Nazi salutes and cries of ‘Hail Trump, hail our people, hail victory!’ for supporters and outlets to understand that the alt-right is just the new face of white supremacy.”

2. The Hubble Space Telescope Advent Calendar

This gorgeous Advent calendar has us all

.

.

3. How to Stay Safe Online: A Cybersecurity Guide for Political Activists

An essential 8-step guide.

If I’ve learned anything since my time in Rome, it’s that people — not just Catholics — are hungering to connect peace with justice. This is why those of us who traveled to Rome just before the election, accompanied by Stockton, Calif., Bishop Stephen Blaire, and Houma-Thibodaux, La., Bishop Shelton Fabre, are preparing for a regional WMPM meeting in Modesto, Calif., in February.

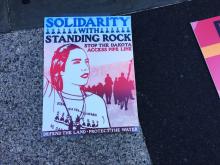

Dec. 4 was a beautiful reminder, in the long struggle for justice, that, no matter how long we wait, God hears our cry. And love and justice will win.

A few weeks ago, Chief Arvol Looking Horse issued an invitation to clergy and faith leaders to stand in solidarity with the people of Standing Rock. He said he was hoping maybe 100 would respond. But I joined thousands, in a procession of faith leaders, to gather around the sacred fire at the Oceti Sakowin Camp at Standing Rock.

I knew something special was happening here.

For many Christians who observe the liturgical season of Advent, leading up to Christmas, an Advent devotional is a beloved companion.

Such devotionals typically include a short Scripture reading and reflection on the birth of Jesus.

But most are “crap,” according to the Rev. Jason Chesnut of Baltimore.

For the last two thousand years, our salvation has come via that peaceful, sleeping baby, weary from being a tiny human. A revolution for a better world begins from the most ordinary of miracles, from small, gasping breaths after a good cry. This is where we will rise, those of us hopeless from the election results, from the margins, from the outside, from the ordinary, miraculous moments of our lives.

The intersection between present and future is a tense and frustrating space to live in. Yet, that space makes a demand on us. Faithful moral identity that is not wedded to moral social action misses the Gospel’s kingdom vision.

Perhaps the most important role of the prophet is rousing us from our stupor. When we get tired, when we are weary of resisting, when we are told over and over again that this is how things are going to be, the prophet’s call is clear. God has something better for us. Something liberating. Something just. Something transformative.

Why and how did Greg’s post resonate with so many people on the meme’s second time around the Internet? Why did it take so much darkness before something profoundly positive happened? I think I come back to two powerful resources available to us as a church, if we have the courage to embrace it.

But perhaps the reason why the darkness cannot understand or overcome the Light is because it will not and cannot imagine reducing itself or condescend to be like its enemy in order to overcome it. Scripture describes an adversary who wanted to be like God, but doesn’t seem to understand that God’s very nature is “gentle and humble and heart.” The nature of darkness is not a generous one. It doesn’t offer light or heat or allow other things to grow. It isolates.

For the longest time, I was convinced that Paul the evangelist totally whiffed on one of his most beautiful passages: the one where he emphasizes that love is what really matters, and then lists some of its defining traits. He starts out by saying that love is … patient.

Really?

He goes on to list other traits, such as kindness. He also says what it’s not: rude, selfish, snobbish, brooding, quick to give up on someone. And it’s all really good stuff, written with such grace. But I’ve always had a difficult time with that first word.

Patient. Love is patient.

If Donald Trump had been Pharaoh of Egypt, the Holy Family never would have escaped from Herod’s persecution. Jews would have been prohibited from entering the country. Christmas features the story of a family from the Middle East leaving a homeland in fear and seeking refuge is a foreign land, just as millions do today.

If you visit Egypt and its ancient Coptic Church, you’ll see images of the Holy Family everywhere: Joseph, Mary — always on a donkey — and the infant Jesus. They are moving, wandering. You’ll find pictures of them passing by the pyramids. Egyptian Christians treasure this story for theirs is the land that offered welcome and hospitality to the Son of God when he was a refugee.

For the first week of Advent, my wife Amy preached about hope. She pointed out that having hope doesn’t mean necessarily that we see a way out of suffering. It does, however, give us a reason to try to keep working through it. We have to believe there’s another side to it. Another possibility. The potential for a new reality.

And that reality will never, ever be realized by responding to violence with more violence. It may make us feel better in the moment. It may seem to offer short-term relief. But ultimately, it makes everyone that participates become a little bit of what they hate. And the cycle continues.

Which story will we choose to try to live into?

I wonder if God calls us to celebrate waiting because the lie we’re all most susceptible to is that if we just get what we want, we’ll be ok. When this is our mentality, we actually forget to live. We become so future-oriented that we can ignore the presence of God in our midst and the signs of the Divine work in this world. We can miss out on the good things he provides daily, hourly.