Black Church

This past spring, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary laid off Rev. Emmett G. Price III, a popular professor and former dean of chapel who founded the Institute for the Study of the Black Christian Experience there in 2016. The decision not to renew his contract as part of budget cuts prompted letters of protest from alumni, community leaders, and the Hamilton, Mass., campus’ student association. But students had been raising concerns about racism on campus with senior administrators for months, Sojourners has learned.

SOMETIMES I WONDER if my “Black card” is in jeopardy. The main source of this concern is that my encounters with the Black church are few, the most consistent being the yearly family viewing of the 1996 film The Preacher’s Wife, though even I know the brevity of that movie’s scripted sermons is far from accurate. My few in-person Black church experiences taught me the basics: Wear your Sunday best, and expect the service to be long. But beyond that, the Black church has always been a bit of a mystery to me, a place that has never felt familiar.

Yolanda Pierce’s In My Grandmother’s House provides an intimate entry into this world. From tarry nights and foot washing to patriarchal structures, Pierce details her experiences and invites the reader into the tension of celebrating the beautiful aspects of the Brooklyn Holiness-Pentecostal church of her youth while also laying bare the ways in which that church, and the Black church at large, has failed to be the loving and inclusive body it professes to be.

In the preface, Pierce describes her book as “a work of Grandmother theology,” a womanist theology that draws on the generational wisdom of older Black women and provides a different way to know God. With the childhood stories she tells, Pierce seems to identify her grandmother Vivian—the woman who raised her, served faithfully in the church, and whose home displayed a portrait of a Black Jesus—as the primary theologian in her life. In a culture that so often elevates the thoughts and analysis of white, male theologians, to read and reflect upon the lessons that Pierce learned from her grandmother and her church mothers makes an impact, lessons that continue to inform how she lives today.

If we are going to overcome vaccine hesitancy and achieve equitable distribution of the vaccine, the Black church will have to take the lead in advocacy for our people who have been among the hardest hit, messaging accurate medical information, and providing greater vaccine access.

A Shared History

Based on Andrea Levy’s novel of the same name, The Long Song depicts a young woman coming of age in Jamaica, anticipating the imminent end to slavery and her servitude. The series displays Britain’s colonial history with the island and crafts a gripping rendering of survival, insurgence, and joy. PBS.

Radical Repair

Decolonizing Discipline: Children, Corporal Punishment, Christian Theologies, and Reconciliation presents practices from Indigenous experts to repair the harm children have endured due to colonial legacies. Edited by Valerie E. Michaelson and Joan E. Durrant, this practical book reimagines raising children. University of Manitoba Press.

In many ways, Seele and countless others who forged the Black church’s response to HIV/AIDS laid the foundation for an effective and powerful faith-based response to COVID-19.

On the 155th observance of Juneteenth, a collective of Black church pastors and theologians released a theological statement to “emphatically repudiate the evil beast of white racism, white supremacy, white superiority and its concomitant and abiding anti-Black violence.”

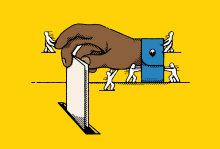

FROM THE SOUTH CAROLINA Democratic primary onward, the votes for the presidency cast by black churchgoers will be criticized by many white people. Even now, black churchgoers’ feelings are speculated about in the press, like in-progress crimes announced on a police scanner.

Media and election pundits ask: “Are they going to choose Joe Biden because of his relationship with Barack Obama? Are they going to go for Elizabeth Warren because of her plan to give $50 billion to historically black colleges and universities and other minority-serving institutions? Are they going to bypass Pete Buttigieg because he’s gay?”

The latter question is the most problematic—an attempt to deem all black churchgoers as homophobic, as if homophobia is something no other racial, ethnic, or religious group has played a part in; as if there’s no such thing as the black grandfather who accepts his gay grandson; the black grandmother who always asks how her grandson’s boyfriend is doing; or the black grandmother who puts on her “good wig” to hang out with said boyfriend when he visits the South. All three are my Christian grandparents, and they’re not alone.

But the most problematic aspect of the Buttigieg question is what it reveals about white sight: Black churchgoers of the electorate are seen as tools to bring about a desired election result, and scapegoats if the election doesn’t go the white way.

Kanye West draws upon the storied history of black communal worship and gospel music.

Toni Morrison understood that belief and faith are substantial to the sustaining force of black folks navigating both slavery and post-slavery traumas.

Fear became slaveholder religion’s tool of control, inspiring millions of poor white families in the South to send sons to war and pray for victory, even as the white sons of plantation owners avoided combat. During Reconstruction, when black and white representatives worked together in Southern legislatures to guarantee public education for all people, many poor white children went to school for the first time; many poor white people received healthcare at Freedman’s Bureau hospitals. Still, their preachers told them to be afraid. Even when black power helped poor white people in measurable ways, slaveholder religion taught white people to fear shared power.

Because of this immense history, power, and influence despite generations of ill treatment and racism, black churches need to thrive, continuing to speak truth to power and serve black communities beyond the sanctuary.

Whatever faults Black Protestantism has had, its grand strength is in its exercise of democratic debate internal to black Americans about the meaning of the good life and who gets a say in the shaping of that life, including perspectives from other faiths.

JUST WEEKS before the fire, I was in front of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, walking around the exterior and enjoying the architecture and ornate sculptures depicting stories of the Christian faith. I didn’t go inside, and I may never have the chance because of how long it will take to rebuild Notre Dame. The iconic wooden spire and roof are gone, as experts try to assess how to support the remaining structure and make it safe. There is international support and money to rebuild, because it appears a tragic accident has destroyed a place that is considered sacred even to those who consider themselves secular.

And that is why so many of us should keep going back to why the burning of three black churches in Louisiana didn’t fill 24-hour news cycles or make us—me—stop and turn on the news.

This is the burden of black women who carry the cargo of worshipping Jesus under the leadership of sexist men. This is the heavy load that Aretha carried throughout her life – being ostracized by men for singing the “devil’s music” while clinging desperately to the message of her father’s teaching. Throughout her life, Aretha paid her tithes and offerings to churches that failed to embrace her full humanity. They elevated the perception of her unholy ways while accepting those checks.

The American Church’s division in our understandings of Jesus neatly follow the fault lines of American society. We hunker in our social groups, worshiping isolated from each other, hearing from preachers who talk like us, and so we natural come to assume Jesus is like us, in talk and in thought.

After a year of verbal brutality, racially charged speeches, and regressive policy proposals, Trump attended a black church in an effort to convince African Americans he is not racist. His trip to Detroit with Ben Carson was the photo op that such an effort demands. Though he was shrewd enough not to say the words, the whole spectacle was designed to say, “some of my best friends are black.”

African-Americans often express frustration at white Americans for overlooking their grief at the deaths of young black men shot and killed by police.

On a conference call last week, hours before Micah Xavier Johnson, a black man, opened fire and killed five white police officers, about 500 Christians, black and white, tried to bridge that racial divide.

As a black, same-gender loving woman, who is a pastor, Bishop and activist, I can solidly say that my wife, children, grandchildren, and community have stronger allies, greater opportunities, and more protections than we have ever had. This is in many ways attributable to a growing number of black clergy who are no longer willing to stand idly by and watch large segments of the communities they were called to serve alienated, stripped of rights, physically abused, and treated unjustly. They have taken the costly stand against the notion that LGBTQ people are unworthy of God’s love and full acceptance within the church.

Police are stepping up patrols and trying to develop a profile of whomever has set six fires outside churches in predominantly black neighborhoods since Oct. 8, Police Chief Sam Dotson said.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri and the Anti-Defamation League suggested a racial motive may be at play. In a prepared statement, the ACLU of Missouri’s executive director, Jeffrey Mittman, called the fires “domestic terrorism.”

“It is a sad truth that, throughout our nation’s history, African-Americans often have been met with astounding violence when they demand equality,” he wrote.

“Those who commit this violence seek to instill fear. This is why arson against predominantly black churches has been a frequent tool of white supremacy.”

A reward of up to $2,000 is being offered for information leading to the arrest of the culprit in a string of fires that have now hit six predominantly African-American churches in and around St. Louis.

Ebenezer Lutheran Church, at 1011 Theobald Street, is the latest church to report damage.

Capt. Garon Mosby, spokesman for the St. Louis Fire Department, said members of the congregation called authorities about 9:25 a.m. Oct. 18 after arriving for a worship service and noticing damage. The fire was already out by the time firefighters arrived, Mosby said.

Although he could not provide additional details, Mosby said that the damage was not extensive. But that the incident was being investigated along with the five other church fires that have happened in the area since Oct. 8.