Catholic Church

“JUST WAR IS KILLING US! There is no just war.”

That proclamation by a Catholic sister from Iraq, and others like it, resounded at a Vatican gathering this spring and fell on surprisingly receptive ears.

Sister Nazik Matty, an Iraqi Dominican, joined others from around the world in Rome in April to wrestle with how the Catholic Church could “recommit to the centrality of gospel nonviolence.” She has watched members of her religious community die for lack of medical care during war.

“Which of the wars we have been in is a just war?” asked Sister Matty, who was driven from her home in Mosul by ISIS, also known by the Arabic acronym Daesh. “In my country, there was no just war. War is the mother of ignorance, isolation, and poverty. Please tell the world there is no such thing as a just war. I say this as a daughter of war.”

The Rome gathering on Nonviolence and Just Peace was unprecedented, bringing together members of the church hierarchy with social scientists, theologians, practitioners of nonviolence, diplomats, and unarmed civilian peacekeepers to discuss Catholic nonviolence and whether in the contemporary world armed force can ever be justified.

Of course, with such diverse participants, there was not a common mind on whether just war theory, a doctrine of military ethics used by Catholic theologians, has outlived its usefulness as church teaching.

Some of the academics and diplomats—particularly from the United States and Western Europe—maintained that just war criteria, when properly applied, are useful when working within halls of power, from the Pentagon to the United Nations, for restraining excessive use of military force by a state. One participant cautioned against “broad condemnations of just war tradition, if it means closing off dialogue with our allies.” Another questioned how diplomacy could continue without the just war framework as its common language.

But Catholics who came to Rome from conflict zones—Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Palestine, Colombia, Mexico, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, and Uganda—brought a different perspective.

“I am a sinner. This the most accurate definition. It is not a figure of speech, a literary genre. I am a sinner.”

It would be presumptuous, from my position of reserve, to make sweeping declarations about what Christianity needs. But I've come to realize what I need from Christianity — a call to action, not permission to engage in the quasi-gnostic pursuit of personal fulfillment.

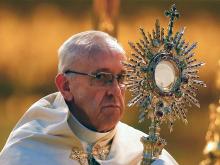

Pope Francis, leading Catholics into the season of Lent, urged people on Wednesday to slow down amid the noise, haste, and desire for instant gratification in a high-tech world to rediscover the power of silence.

“Dog, cats, and motorcycles get blessings, but we’re not worth one?” Mayor Peter Hinze complained. “It can hardly be made clearer that we’re second-class people.”

LAST APRIL, El Salvador became the first country in the world to ban the mining of gold and other metals. The action grew out of a decades-long struggle to protect access to clean water and prevent pollution caused by mining projects.

The Catholic Church played a central role in the movement to end mining, which organized under the slogan Si a la vida, no a la mineria (“Yes to life, no to mining!”). An encyclical from Pope Francis provided inspiration, and San Salvador’s archbishop called on legislators to pass the anti-mining law, which the church was integral in writing. For many, it called to mind the actions of Archbishop Óscar Romero in El Salvador’s civil war decades before.

‘To work for the mines is to work for death’

Beneath the jungles and mountains that stretch from southern Mexico to Nicaragua lie untold mineral riches. Over the last two decades, transnational companies, drawn by the lack of regulation and the promise of huge profits, have sought to exploit these resources. But the rise of the extractive industries has triggered intense social conflicts, environmental destruction, and violence throughout the region.

The pope spoke of “faithful creativity” in responding to a rapidly changing world. The job of a theologian is to show people what lies at the heart of the Gospel.

AMONG THE MANY hopeful initiatives to come from the Vatican under Pope Francis is an attempt to rebuild the church’s relationship with the arts. Francis declared this to be among his priorities in his famous 2013 interview with Jesuit priest Antonio Spadaro (published in the U.S. by the journal America). Francis listed among his inspirations painters Caravaggio and Chagall, the Russian novelist Dostoevsky and the German poet Friedrich Hölderlin, the music of Bach and Mozart, and the films of Fellini and Rossellini.

Lately the pope’s passion for art has taken tangible form with an interview-based book in Italian, whose title translates to My Idea of Art, and a documentary film of the same name, subtitled in six languages, that tours the Vatican Museum’s artistic treasures. In the book, Pope Francis argues that great art can serve as an antidote to contemporary greed, exclusion, and waste and maintains that “a work of art is the strongest evidence that incarnation is possible.”

Pope Francis came to office determined to downgrade some of the papacy’s pomp and splendor. He lives in a guest house instead of the papal apartment. He wears sturdy black walking shoes instead of those iconic red slippers and a silver cross where his predecessors went for the gold. He seems like the sort who might auction off the Vatican’s art collection and give the money to the poor.

But Francis instead sees the church’s involvement with the arts, past and present, as an occasion for evangelization.

In an apostolic letter read in Latin by Amato and English by Oklahoma City Archbishop Paul S. Coakley, Francis praised Rother as a priest and martyr “who was driven by a deeply rooted faith and a profound union with God, and by the arduous duty to spread the Word of God in missionary lands.”

“It’s hard to really put into words,” said Marita Rother, a nun and younger sister of the priest who was shot to death on July 28, 1981, while serving as a Catholic missionary during Guatemala’s bloody civil war.

“I think the whole thing is beyond what any of us would expect to be happening,” she added.

Pope Francis has defrocked an Italian priest who was found guilty of child sex abuse, three years after overturning predecessor Benedict XVI’s decision to do the same after allegations against the priest first came to light.

Mauro Inzoli, 67, was initially defrocked in 2012, after he was first accused of abusing minors, but Francis reversed that decision in 2014, ordering the priest to stay away from children and retire to “a life of prayer and humble discretion.”

One of the most senior officials in the Vatican took a leave of absence and pledged to defend his name after being charged with multiple historical sex crimes in Australia.

Cardinal George Pell, one of Pope Francis’ most trusted advisors and head of the Holy See’s finance department, is the highest ranking official in the Catholic Church to face abuse charges.

Prominent U.S. ethicists are among a number of international experts chosen by Pope Francis for his bioethics advisory board — a move that might temper the group’s conservative views on sexual morality and life issues.

The same week that President Donald Trump was meeting with Pope Francis in Rome, another historic event was taking place, as the Global Christian Forum facilitated a groundbreaking encounter with the major global bodies representing most every part of world Christianity.

Twelve Catholic priests and brothers live, work, and pray at the Vatican Observatory as they explore some of the universe’s biggest scientific questions, from the Big Bang theory to the structure of meteorites and stars.

“The observatory exists to show the world that the Catholic Church supports science,” says Brother Guy Consolmagno, an astronomer from Detroit who is also the observatory’s director.

Based near the town of Merced in the Central Valley, which produces over half of the fruit, vegetables, and nuts grown in the United States, the Sisters of the Valley grow and harvest their own cannabis plants.

Pope Francis condemned the suspected chemical weapons attack that killed over 100 people in Syria and renewed his call for an urgent political solution to end the war. Speaking at his weekly audience at the Vatican on April 5, the pope said he was horrified by the “unacceptable” massacre of civilians, including at least 20 children, on April 4.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks made a name for himself as chief rabbi of Great Britain for nearly a quarter-century, a time of great tumult that included the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks, the influx of millions of Muslims into Europe, and the ongoing pressures to absorb and assimilate newcomers into a mostly secular society.

As chief rabbi, from 1991 to 2013, he stressed an appreciation and respect of all faiths, with an emphasis on interfaith work that brings people together, while allowing each faith its own particularity.

“There is simply no justification in our day for failures to enact concrete safeguarding standards for our children, young men and women, and vulnerable adults,” O’Malley said.

“We are called to reform and renew all the institutions of our church. … And we certainly must address the evil of sexual abuse by priests.”

As Pope Francis marks the fourth anniversary of his revolutionary papacy, the pontiff apparently finds himself besieged on all sides by crises of his own making: an open “civil war” in the Catholic Church and fears of schism, mounting opposition from the faithful, and a Roman Curia so furious with his reforms that some cardinals are plotting a coup to topple him.