death

My friend Mike died last week.

We were the same age. We grew up together in Marinette in northeast Wisconsin. Worked our way through Boy Scouts together. Played at each other’s houses. Studied in the same classrooms. And then, over time, we drifted apart. Until this past year. That’s when I learned that Mike was dying of cancer.

In less than 12 months, we re-established a friendship and Mike and his wife, Nancy, taught me amazing lessons about living with the prospect of dying.

In our initial contacts, Nancy wrote of Mike:

“He is doing well with his treatments. I am amazed, each day, how well he handles this journey we are on. Never once have we asked ‘why us?’ We feel so blessed that we have each day to love each other and enjoy our retirement one day at a time. Not everyone is so lucky to have a long goodbye with the one they love.“

“O Lord, our Sovereign, how majestic is your name in all the earth! You have set your glory above the heavens.” And from those heavens descended a deadly cloud.

“Out of the mouths of babes and infants ...” The children of Plaza Towers Elementary?

“What are human beings that you are mindful of them, mortals that you care for them?” Indeed that is the question that troubles the heart of the faithful in times like these.

Can we still praise God? If so, how do we start? Can we possibly understand what happened in Moore, Okla.?

Don’t trust anyone who claims to comprehend the meaning of this storm. Don’t trust anyone who points with absolute certainty to a single cause for this storm. Don’t trust anyone who treats a tornado as anything but indiscriminate and cruel. These tragedies are not punishments or object lessons. Such natural forces do not reach their conclusion with a pat moral or a simple “they lived happily ever after.”

THE SAGA OF Elijah that we are following in 1 and 2 Kings culminates in a poignant parting as the prophet prepares to be taken up into heaven. His disciple, Elisha, makes a final all-or-nothing request: “Please let me inherit a double share of your spirit” (2 Kings 2:9). Elijah states a condition for the fulfillment of Elisha’s prayer: “You have asked a hard thing; yet, if you see me as I am being taken from you, it will be granted you; if not, it will not” (2:10). It is as if Elisha has to look unblinkingly into the reality of their separation. If he is to inherit the prophetic mantle and spirit of his teacher, he must claim the vocation in its entirety. He is now to be the prophet.

The story is an uncanny pointer to the truth that John the Evangelist highlights in Jesus’ last words to his disciples: “I tell you the truth: It is to your advantage that I go away, for if I do not go away, the Advocate will not come to you ...” (16:7). John even echoes the “double spirit” theme in 14:12, when he has Jesus assure us that our prophetic endeavors will be more abundant and powerful than Jesus’ own!

The season following Pentecost helps us realize that we are the prophets now, vested with the mandate and endowed with the gifts for enacting the good news of liberation.

Yesterday Kay Stewart shared this at the cemetery as we laid to rest the ashes of her first-born daughter Katherine (“Katie”).

For Christ to have gone before us,

To have kept us from ultimate sadness,

To be our brother, our advocate,

The One who ushers in the Kingdom,

Here

And the One to come,

Does not keep us from our digging today.

We still gather here and throw the dirt on our sacred dust,

We take the shovel like all those gone before us

And surrender to the Unknowable—

The place where

Love and Beauty and Kindness grow wild.

Where sorrow has no needs,

Where there is all beginning and

Nothing ends.

...

Here in the Upper Midwest (I live in Minnesota), the importance of higher ground is not just metaphorical, as snowmelt-fed flood waters rise to envelope communities. People, quite literally, are forced to higher ground by floods.

It is interesting, too, what happens when that higher ground, the literal higher ground, is sought. Necessarily, there are more people in a smaller area; that’s the nature of it. Diverse groups are forced together. We know these images from the news: the floating cars, and then the displaced people together in a school gym, talking. The power of that second image is that it shows an unexpected, shared space. People have grabbed what they could and fled to this place, often by walking uphill, and now they find themselves together.

When the metaphorical waters rise and destroy what we know or count on, people do the same thing, but that higher ground is a broad mutual faith that encompasses the belief that there is something greater than ourselves, that there must be a reason for these tragedies; we turn to God. Recently, we have seen this happen in Boston and in West, Texas. At the memorial for the victims of the explosion in West, held at Baylor University, President Barack Obama spoke openly about faith.

No one wants to talk about death at the dinner table, at a soccer game, or at a party, says Lizzy Miles, a social worker in Columbus, Ohio.

But sometimes people need to talk about the “taboo” topic and when that happens, they might not be able to find someone who will listen, she says.

“Whenever people hear I’m a hospice worker, they talk to me about death. It doesn’t matter if I’m on an airplane, gambling in Las Vegas, or in a grocery store line,” she said. “I really see firsthand the need to let people talk. It’s my gift to others.”

Her gift sparked the birth of “death cafes” in the U.S., a trend that started in England and is about to take off across America, she said.

The common good is not only about politics. The common good is about life and how we live it. It is ultimately about how we are all connected. It is about how our love or lack of love affects our families, our neighbors, our communities, our cities, our nation, and our world.

The common good is about personal brokenness. Have we taken the time to let Jesus come in and heal the wounds that distort the image of God within of us — wounds that drive daughters and sons, mothers and fathers to self-destruction? Have we taken the time to let the Great Physician heal the personal wounds that break families and friendships, slicing the central fabric of society? We are all connected.

WHEN A COLLEAGUE told me Sojourners had received a review copy of the latest Thursday Next novel by Jasper Fforde, I was delighted—and confused. My delight came because I’m a huge fan of the series, whose protagonist Thursday lives in an alternate-reality U.K. and, in previous novels, has worked for Jurisfiction, the policing agency within fiction. My favorite scene was when, several novels back, she helped Great Expectations’ Miss Havisham moderate an anger management group in Wuthering Heights, set up to keep it from going the way of “that once gentle comedy of manners, ‘Titus Andronicus.’”

However, it was unclear why anyone would send a book from this series to a Christian social justice-oriented magazine. My best guess, as I gleefully devoured The Woman Who Died A Lot, was that some hilariously over-optimistic publicist thought we’d be interested in the novel’s subplot in which God reveals Godself by smiting various cities with columns of fire—sometimes in response to sin, sometimes to “unimaginative architecture, poor restaurants, or even an overly aggressive parking fine regime.” Thursday’s hometown of Swindon is next on the smite list, possibly to increase God’s bargaining position against the locally based Global Standard Deity church. The GSD, having unified the world’s religions, plans to use its “collective bargaining powers” to open formal negotiations with God, starting with the question, “What, precisely, is the point of all this?”

If I were Brian McLaren, I could no doubt get mileage out of this negotiating-with-God idea, and out of the novel’s various speculations about whether notbelieving might make God (or, in a separate subplot, an asteroid hurtling toward the Earth) cease to exist. Other storylines—a villain who can alter memories convinces Thursday she has an extra child; Thursday’s teenage son Friday is apparently fated to murder someone who may or may not be an irredeemable louse—could, at a stretch, fuel theological debate about identity or free will.

Whom Shall I Send?

Drawing on years of pastoral and executive experience in churches and parachurch organizations, Sherry Surratt and Jenni Catron deliver on the pragmatic promise of their book's title, Just Lead! A No Whining, No Complaining, No Nonsense Practical Guide for Women Leaders in the Church. Jossey Bass

Giving Thanks

Dreams. Wind. Bread. Oriental rugs. Puppet shows. These are a few of the inspirations for Benedictine Brother David Steindl-Rast's 99 Blessings: An Invitation to Life. These short, concise, sometimes whimsical prayers of gratitude for gifts great and small are invitations to increase our awareness of life's daily wonders. Image

IN THE EARLY weeks of the Eastertide lectionary, there appears a series of texts from the third and fourth chapters of Acts ... Peter and John, on their way to temple prayers, heal a man begging at the beautiful gate. His joy begets a sermon from Peter on the resurrection, at the close of which the disciples are arrested and spend the night in jail. The next day in court they again testify boldly, refuse to comply with the court's order, and are released after calculated threats from the authorities. Their release prompts prayers of thanksgiving in the community.

“What? What happened?” My co-worker asked, sensing the solemn look on my face.

“Another patient died,” I reported. Grief and thick silence hang in the air as I thought back to the last time I saw this person, hospitalized, unable to speak, but for a brief moment our hands met in an embrace, and although he couldn’t speak, his demeanor and soft touch of the hand said it all.

I brought myself back to the present moment. It was the end of the work day and I strapped on my helmet to bike home, a Lenten commitment I’ve found to be incredibly rejuvenating.

I pedal past the housing projects and turn the corner around the city jail. Activists holding bright colored placards protest peacefully against the death penalty. I smile at them. “Keep up the good work!” I enthuse, giving them a thumbs up from my navy blue mitten and pedal on my way.

A second later, it hits me. Tears rush to my eyes but refuse to come out. The taut muscles in my throat contract; that familiar lump in which no words can come out, just expressions of the heart. Yes, it hit me.The juxtaposition and irony of it all. Life and death. One man died today from four letters that no one should ever have to die from, but globally, some 1.8 million do every year. Another man protested for the life of another to not be cut short before the redemption and healing and forgiveness began.

I awoke in the middle of the night last evening and walked the house in the dark. Kenneth and Caitlin were still stirring, as the older children sometimes do on the weekend. As I climbed the stairs back to our room I felt a wave of gratitude.

Here we are all under one roof for who knows how much longer, yet such a privilege to still be together even as four of seven attend college and work hard and make us proud as they figure out what's next.

I got back into bed and Debbie put her arm around me in her sleep. I said "I love you," and she whispered, half-asleep "I love you, too," and for that moment all was well, and I had a sense that all would be well in the future, come what may.

As I lay there in the stillness, an encounter from five years ago came back to me in vivid color. I had just preached the funeral of a man taken unexpectedly following a routine surgery. I was at the wake afterward and sat next to an unassuming man in his mid-50s whose suit was impeccable and whose polite manners suggested a quiet grace and a bearing of humility in his obvious accomplishments, but also a bit of world-weariness.

“After the first exile, there is no other.”

—Rosellen Brown, The Autobiography of My Mother, 1976

The great wheel of the year has turned once more, and I find myself back at the beginning again. Not at the start of a brand new year, but rather, at the anniversary of my father’s death.

I was eight years old when he died, on January 8, 1977, after six long months of decline from lung cancer. In the family’s last-minute midnight scramble to the King’s Daughters Hospital to offer a final farewell, I was adjudged too young and too asleep to wake up for the ride.

I found out that he had died when I crawled from bed at dawn the next morning, yawning and jonesing for cartoons, only to find a bath robed neighbor stoking the fireplace, and my father disappeared into ether.

That singular fact has been the still point of my turning world in the decades since.

October was Interfaith Month for Prop 34, a time set aside for leaders of faith traditions to address the question of California’s death penalty and advocate for its replacement. Hundreds of faith community’s have endorsed Proposition 34 because we believe the best way to do justice in California is to replace the death penalty with life in prison with no possibility of parole.

The will to see justice done is deep within the human spirit. We may not always agree on what “justice” looks like, but the belief in a just and fair society — and the desire to bring it about — are at the heart of how we live together and form a community. In religious traditions like Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and countless others, doing justice is a calling to enact God’s will.

The next question is, of course, what does that mean? Discerning justice can be even harder than doing justice.

Quantum Theory is still in its relative infancy within the entire discipline of science, although it finds its roots as far back as Plato and Descartes. But if some of the notions being pursued by contemporary scientists prove true, it may result in a convergence of science, art, philosophy, and even religion that the world never imagined possible.

I’ll admit from the start that investigating the literature for this particular article literally made my head hurt. To fully conceive of all that is discussed and examined in Quantum Theory takes a scientific sophistication that I lack. But fortunately there are some out there who are trying to make these complex ideas more digestible, without a string of letters after our names.

One such scientist is Stuart Hameroff, Professor Emeritus at the Department of Anesthesiology and Psychology and the Director of the Center for Consciousness Studies at the University of Arizona. To distill a very complex idea down into a few words, the general consensus in science is that consciousness can be attributed to computations conducted within the neurological networks in the brain. Basically, all consciousness can be explained by algorithms, which makes our brains essentially like big, highly sophisticated computers. There are some limitations thus far to this perspective, such as how such algorithms account for things like aesthetic experience, love, and even our sense of smell. Researchers in the area of Artificial Intelligence believe that discovering the algorithmic bases for such phenomena can lead to the construction (given the necessary technology) of an artificial human brain.

Coptic Christian leaders in the United States distanced themselves from an anti-Muslim film that has sparked protests in more than 24 countries, and denounced the Copts who reportedly produced and promoted the film.

"We reject any allegation that the Coptic Orthodox community has contributed to the production of this film," the Coptic Orthodox Archdiocese of America said in statement on Friday.

"Indeed, the producers of this film have taken these unwise and offensive actions independently and should be held responsible for their own actions."

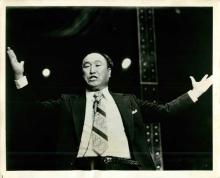

The Rev. Sun Myung Moon, revered as a messiah within his Unification Church but regarded by many others as a vain and enigmatic man who blessed mass weddings, built a sprawling business empire and presided over a personality cult, died on Monday in South Korea. He was 92.

Moon had been in intensive care at a Seoul hospital since Aug. 7, according to his church. The cause of death was complications from pneumonia, including kidney failure.

Moon was born in 1920 in what is now North Korea, and rose from a home in which five siblings starved to death to become an ambitious man who harbored a lifelong hatred of communism, craved respect from the rich and powerful and professed a divine mandate to restore a fallen world.

In the recent past there was a small group of children gathered in the village of Tucville, located near Georgetown, Guyana. After a few hours of games on the street, the curious crew wandered away from adult supervision and explored a nearby abandoned sewage facility. The children enjoyed their playful investigation, but as they walked a narrow path near the edge of a raw sewage container, a 5-year old girl named Briana Dover accidentally slipped, fell, and quickly sank to the bottom.

As to be expected, Briana’s friends immediately screamed and ran for help, but as neighbors and witnesses rushed to the site, they all stood in shock. Although some considered diving into the tank, no one stepped forward. The container was too large, the smell of rotten feces too disgusting, and the actions required far too dangerous. With each passing moment Briana held to the brink of life at the bottom of the sewage reservoir, moving closer to death with each tick of the clock.

In the meantime, a middle-aged Rastafarian named Ordock Reid heard the commotion. After initially thinking it was a worker dispute, he eventually examined the situation, and as he approached the tank, he was greeted with loud screams and anguished faces. When he was told about Briana’s predicament, he acted immediately. Ordock Reid – a total stranger – took off his clothes, tied-up his dreadlocks, fastened a rope to his waist (handed the other end to an onlooker), and submerged himself through the muck and filth in an attempt to rescue Briana Dover.

“It was like a scene out of a movie.”

I’ve heard that phrase a few too many times in the past month.

On June 26, after the third consecutive 100-plus-degree day, residents of northwest Colorado Springs fled their neighborhoods with a few belongings shoved in their cars as a wildfire came barreling down the mountainside. The billows of smoke and inferno flames, calculated to be three stories high, could be seen from anywhere in the city. It was like a scene out of a movie.

In the early morning hours on July 4, I received the text that I had been dreading: “Cliffy is with Jesus.” After a six-year battle with cancer, my biggest cheerleader, friend, and mentor, Cliff Anderson, died in hospice. Two months prior, Cliff was sharing his wisdom and offering his typical words of encouragement at a retreat for GreenHouse Ministry, an intentional community that we started together in Colorado Springs. But shortly after that weekend the diagnosis became clear. This incurable type of cancer was going to win, sooner rather than later. Watching his decline felt like watching a tragic movie.

At the midnight premiere of the new Batman movie, Dark Night Rises, on July 20 in a suburb of Denver, a gunman opened fire on a packed theater, killing 12 and injuring more than 50 people Witnesses to the shooting said it was like something out of a movie. The scene was an eerie echo of another mass shooting in a different Denver suburb 13 years ago at Columbine High School. Could this really be happening again?

In a poignant first-person essay in today's LA Times, actor and director Ron Howard, who as a child played Opie on The Andy Griffith Show, tenderly remebers his mentor and friend Andy Griffith, who died Tuesday at the age of 86.

Howard recalls:

He was known for ending shows by looking at the audience and saying "I appreciate it, and good night." Perhaps the greatest enduring lesson I learned from eight seasons playing Andy's son Opie on the show was that he truly understood the meaning of those words, and he meant them, and there was value in that.

Respect. At every turn he demonstrated his honest respect for people and he never seemed to expect theirs in return, but wanted to earn it....