Diversity

I MET PASTORS Harvey, Alton, Charles, and Joel in Houston’s 5th Ward, a black neighborhood that in 1979 earned the title of “the most vicious quarter of Texas.” I was drawn there by a sermon I’d preached on Psalm 23 called “An experiment in crossing borders.” In it I asked my congregation, “What border is God leading you to cross? And who is waiting for you on the other side?”

Little did I know the profound impact that sermon would have on me.

Nearly five years later, I remember when these men stopped being “pastors at black churches on the other side of the 5th Ward border” and became “my people,” deeply connected as members of the body of Christ.

It was a moment of profound truth-telling, when I realized I was controlled more by the values of Western “racialized” culture than I was by the liberating gospel of Jesus and the alternative community to which I had given my life. It became clear to me that I’d affirmed myself and my identity through the lies of racial privilege, and done so at the expense of my brothers and sisters in Christ.

Michael Emerson, a sociologist from Rice University, provides us helpful language to understand how race works. Rather than analyzing racism (concretized for most of us through powerful images of slavery, hooded white supremacists, separate drinking fountains, and individual acts of hate), he invites us to analyze how our society is racialized.

On Oct. 13, Asian Americans United published an open letter asking the church to reevaluate its behavior toward its Asian brothers and sisters. The letter demands that the evangelical community listen and respect a community that has generally been overlooked or disregarded. Central to this issue is identity.

When we begin to divide or alienate communities through our behavior based on race, we are additionally dividing the identity of Christ. However, if we return to the core of what being Christian entails, we are reminded that we are not our own and find a new calling to community.

With whom do you identify? In a nation, with over 75 percent of its population nominally claiming the label Christian, asking whom we identify with is an important question. It is a challenge but a daily necessity to reflect on our character and ask if we are truly representing Christ.

American Jews say they face discrimination in the U.S., but they see Muslims, gays, and blacks facing far more.

This and other findings from the recently released Pew Research Center’s landmark study on Jewish Americans help make the case that Jews — once unwelcome in many a neighborhood, universitym, and golf club — now find themselves an accepted minority.

“While there are still issues, American Jews live in a country where they feel they are full citizens,” said Kenneth Jacobson, deputy national director of the Anti-Defamation League, which was founded in 1913 to combat anti-Semitism.

The most controversial sentence I ever wrote, considering the response to it, was not about abortion, marriage equality, the wars in Vietnam or Iraq, elections, or anything to do with national or church politics. It was a statement about the founding of the United States of America. Here’s the sentence:

"The United States of America was established as a white society, founded upon the near genocide of another race and then the enslavement of yet another."

The comments were overwhelming, with many calling the statement outrageous and some calling it courageous. But it was neither. The sentence was simply a historical statement of the facts. It was the first sentence of a Sojourners magazine cover article, published 26 years ago titled “America’s Original Sin: The Legacy of White Racism.”

An extraordinary new film called 12 Years a Slave has just come out, and Sojourners hosted the premiere for the faith community on Oct. 9 in Washington, D.C. Rev. Otis Moss III was on the panel afterward that reflected on the film. Dr. Moss is not only a dynamic pastor and preacher in Chicago, but he is also a teacher of cinematography who put this compelling story about Solomon Northup — a freeman from New York, who was kidnapped and sold into slavery — into the historical context of all the American films ever done on slavery. 12 Years is the most accurate and best produced drama of slavery ever done, says Moss.

In her New York Times review, “ The Blood and Tears, Not the Magnolias,” Manohla Dargis says, 12 Years a Slave “isn’t the first movie about slavery in the United States — but it may be the one that finally makes it impossible for American cinema to continue to sell the ugly lies it’s been hawking for more than a century.” Instead of the Hollywood portrayal of beautiful plantations, benevolent masters, and simple happy slaves, it shows the utterly brutal violence of a systematic attempt to dehumanize an entire race of people — for economic greed. It reveals how morally outrageous the slave system was, and it is very hard to watch.

When we consider the typical church worship service in the United States, we discover certain trends. Lament and stories of suffering are conspicuously absent. In Hurting with God, Glenn Pemberton notes that laments constitute 40 percent of the Psalms, but in the hymnal for the Churches of Christ, laments make up 13 percent, the Presbyterian hymnal 19 percent, and the Baptist hymnal 13 percent.

Christian Copyright Licensing International (CCLI) licenses local churches for the use of contemporary worship songs. CCLI tracks the songs that are employed by local churches, and its list of the top 100 worship songs as of August 2012 reveals that only five of the songs would qualify as a lament. Most of the songs reflect themes of celebratory praise: “Here I Am to Worship,” “Happy Day,” “Indescribable,” “Friend of God,” “Glorious Day,” “Marvelous Light,” and “Victory in Jesus.”

How we worship reveals what we prioritize. The American church avoids lament. Consequently the underlying narrative of suffering that requires lament is lost in lieu of a triumphalistic, victorious narrative. We forget the necessity of lament over suffering and pain. Absence doesn’t make the heart grow fonder. Absence makes the heart forget. The absence of lament in the liturgy of the American church results in the loss of memory.

I once spoke to a writing class at a respected evangelical university on the Good Samaritan, a basic message about God’s call to love everyone. In the course of my hour-long lecture, I mentioned the word “slavery” once. One time.

That one mention was met with this one question during the Q-and-A time: “What does slavery have to do with anything?”

The young evangelical proceeded to tell me, “slavery only lasted about 50 years and it wasn’t even that bad. I mean they were better off because of it, right? They got Christianity, didn’t they?”

I learned a survival lesson on that day: Don’t even mention the “s” word to white people. It’s not safe.

But last week, at Sojourners’ Special Faith Leaders’ Screening of 12 Years a Slave, Dr. Barbara Williams-Skinner said something profound during the post-screening panel discussion of the film:

“White people don’t want to talk about what happened,” Williams-Skinner said. “We need racial reconciliation in our nation and in the church, but reconciliation requires repentance and how can we get to repentance, if we can’t even have the conversation?”

We do need racial healing. Our nation needs it desperately.

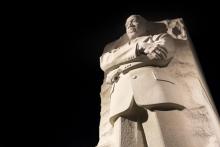

Are we waiting for another Dr. King? As I collect my thoughts to write these words, I’m mindful that I don’t honestly know what discrimination is. I have never (consciously) experienced discrimination because of my race, the color of my skin, or where I come from. I have never had to say, like Solomon Northup, “I don’t want to hear any more noise.” In the film, 12 Years a Slave, Solomon refers to the cry of those being beaten and separated from their children. I speak here with a profound sense of respect and fear. Who am I, or maybe even you who read, to speak about a tragedy and a pain that we have never experienced? I only speak out of a sense of duty and a calling from God.

Dr. King wrote, “So many of our forebears used to sing about freedom. And they dreamed of the day that they would be able to get out of the bosom of slavery, the long night of injustice … but so many died without having the dream fulfilled.” (A Knock at Midnight, p.194)

To this day, millions of African Americans in our country still dream about getting out of the bosom of slavery. Slavery today is masked behind the social, financial, political, and even religious systems that deny the dignity and full integration into these systems to people of color. Solomon Northup cries out in the film saying, “I don’t want to survive, I want to live.” The struggle of African Americans is a struggle to live. So far, they have only survived.

Crickets chirping, a branch creaks, and a black body swings on a tree whose roots grow deep into a shared story of our American past. These are images that are floating in my mind, after watching a pre-screening of12 Years a Slave. This film was a terribly beautiful depiction of the antebellum south and the atrocity known as slavery. Its honesty was riveting, as the film portrays characters in ways never captured before on the big screen. They were characters such as Mistress Shaw (played by Alfre Woodard), the black wife of a slave master who is adored by her husband and treated as a white woman. In a panel discussion, Lisa Sharon Harper of Sojourners asked Woodard, about this character. And she responded that in the South, there were all kinds of arrangements between whites and blacks. Her character Mistress Shaw learned how to survive. I was so refreshed that 12 Years a Slave, was a new depiction of slavery instead of a rehashing of Roots orAmistad.

The panel also consisted of a plethora well-informed faith leaders. One of the panelists, Jim Wallis, while discussing the aspects of faith profoundly said, “Enslaved Africans saved Christ from the Christians.” I was immediately struck by his words as they reminded me of how I became a Christian.

Strange but beautiful things happen when we begin to identify with people who are culturally different. A few years ago, I became friends with Peter, a guy at my church who also happened to be an undocumented immigrant. One day over lunch, he shared that his mother (whom he hadn’t seen in 15+ years) had recently been diagnosed with a terminal disease. He desperately wanted to visit her, but due to his immigration status, he knew that if he left the U.S. he wouldn’t be allowed to return. Given his obligations to his family in the U.S., Peter made the heart-breaking decision to not to visit his dying mom.

As a U.S. citizen, I hadn’t personally experienced the trials of being undocumented or felt the frustration of geographic immobility while a loved one approached death in a far off land. But throughout my friendship with Peter — getting to know his family in the U.S., listening to him share about the harrowing challenges he experienced on a daily basis, and seeing photographs of his life and family in his home country — I got a glimpse of the world from his perspective. In many ways, Peter’s life was marked by sorrow and loss – and that was more evident than ever during our lunch conversation that day.

I pre-screened 12 Years a Slave the same weekend I saw Gravity. The two films couldn’t be more different, although they do have some fascinating (if not immediately obvious) commonalities.

As for commonalities, they’re both powerful and both deserve to be seen. Both are about people trying to get home — one, in a harrowing adventure that takes several hours, the other in an agonizing 12-year struggle. The protagonists of both movies demonstrate heroic resilience and courage. One struggles with physical weightlessness, the other with a kind of social or political weightlessness.

Although Gravity impressed and fascinated me, 12 Years a Slave affected me and shook me up. Now, several days later, scenes from the film keep sneaking up on me and replaying in my imagination — three in particular.

The ethos of slavery still runs deep in our national consciousness. Alfre Woodard, a supporting actress in the upcoming movie 12 Years a Slave, hopes that point is taken by all who see it.

“Whenever there is repression, it takes toll on everyone; especially a physical and psychic, stunting pain on the abuser,” Woodard said at a panel following a pre-screening of the movie hosted by Sojourners last week. “My hope, expectation is that audiences will start to think about slavery in a new way. That they’ll come away with some small perspective to understand each other better.”

The panel gathered to begin the conversation about residual impacts of slavery on the United States. Woodard started the discussion with a description of what it was like to be set and involved with a film that revolves around such a difficult emotional topic.

[view:Media=block_1]

What would the world be like if we were all more alike?

This isn’t just a philosophical question. In many ways, we live as though we wished others were more like us. We spend time with those who are similar to us and avoid those who seem to be different. We enjoy being around those who share our viewpoint and avoid those who challenge it. We accept the parts of others that make us comfortable and ignore or reject the rest.

But what about our diversity? Do we embrace it, or do we merely tolerate it?

Over time, I’ve grown to appreciate the importance of our differentness. I’ve gotten to the point where I think of this incredible diversity — within our universe, within our human family — as one of our greatest blessings.

I watched 12 Years a Slave today. The film is based on Solomon Northup’s autobiography by that name. Northrup was a free black man living in Saratoga, N.Y. He was lured away from his home to Washington, D. C., on the promise of lucrative work and was kidnapped, transported to Louisiana, and sold into slavery. He was rescued 12 years later.

Some of the questions and issues that the movie raises are: What right do people have to own others? Do money and might make right? Unjust laws — such as slave laws — exist. It just goes to show that something can be legal, yet morally wrong. Still, laws come and go. We must not confuse laws with rights, which are universal and enduring truths that do not change. What is true and right and good is always so. So, too, that which is evil is always evil. Even if unjust laws are overturned and abolished, evil can still return in other guises.

I asked myself as I watched the movie, “Could it happen again?” Some of us may think, “Surely, something like this could never happen in our day.” And yet, people are abducted and sold into various forms of slavery here and abroad on a daily basis. Granted — people are not publicly bought and sold on the slave block in America today because of skin color; however, people are enslaved based on race and class divisions.

There are few things as exhausting, draining, and disheartening as family drama. I’m not talking low-level sibling rivalry over who gets shotgun all the time. I’m talking deep-rooted family issues that go generations back. That kind of family drama shows up in the most inopportune times in the most inappropriate places — at someone’s wedding or funeral, at the family reunion, or while grocery shopping.

But when family drama shows up in the church, it grieves me. It riles me up like nothing else does because it is in my identity as a Christian and Jesus-follower where I am all of who God created me to be and has called me to be — Asian and American, Korean, female, friend, daughter, wife, mother, sister, aunt, writer, manager, advocate, activist. The church is the place where I and everyone else SHOULD be able to get real and raw and honest to work out the kinks and twists, to name the places of pain and hurt, and to find both healing and full restoration and redemption.

So when the church uses bits and pieces of “my” culture — the way my parents speak English (or the way majority culture people interpret the way my parents speak English) or the way I look (or the way the majority culture would reproduce what they think I look like) – for laughs and giggles, it’s not simply a weak attempt at humor. It’s wrong. It’s hurtful. It’s not honoring. It can start out as “an honest mistake” with “good intentions,” but ignored, it can lead to sin.

Fortunately, there is room for mistakes, apologies, dialogue, learning, and forgiveness.

Since the production of The Birth of a Nation, Hollywood has lived with the mythic world imagined by artists who view the lives of people of color as footnotes and props. From Gone With The Wind to Django Unchained, the most difficult type of film for Hollywood to get right is the antebellum story of people of color.

Django, for example used the archetypes designed by Hollywood — “Mammy, Coon, Tom, Buck, and Mulatto,” to quote film historian, Donald Bogle — and exploit them in order to create a hyper-exploitation Western fantasy, with slavery as the backdrop. The film is a remix and critique of exploitation clichés, not a historical drama seeking to illuminate our consciousness. Django is a form of visual entertainment where enlightenment might happen through a close reading of the film. All the archetypes remain in place. Nothing is exploded or re-imagined, only remixed to serve the present age.

Steve McQueen’s 12 Years A Slave, on the other hand, sits within and outside the Hollywood fantasy of antebellum life. I say it sits within, because the archetypes forged by the celluloid bigotry of D.W. Griffith are present. But, in the hands of the gifted auteur, Steve McQueen, they are obliterated and re-imagined as complex people caught in a system of evil constructed by the immorality of markets, betrothed to mythical, biological, white supremacy.

Asian-American Christians are voicing concerns over how they’re depicted by white evangelicals, most recently at a conference hosted by Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church in California.

Saddleback recently hosted a conference by Exponential, a church-planting group, and a video last Tuesday left some Asian-Americans offended.

It’s the second dust-up in as many months involving Asian-Americans and Warren, who spoke at the Exponential conference. Last month he received backlash from Asian-American Christians after he posted a Facebook photo depicting the Red Guard during China’s Cultural Revolution. “The typical attitude of Saddleback Staff as they start work each day,” the caption read on Sept. 23.

I love October. As a teacher, it was that time of year where rhythms were becoming established and the seeds of learning were beginning to sprout. In ministry, it is the time where I find myself riding the waves of my student’s school schedules in an effort to connect and converse. In either case, education, shapes not on the schedule of my life but the purpose.

As I breathe in the crisp autumn breeze, it reminds me to consider the larger partnership between the educators and the church. When we, as ministers and church leaders, consider what role education plays in the life of the church, we have to consider the active part of the church in the education of not only the church community, but its larger context.

Education, in the public context, is a constant topic of political struggle and strife. Education, in the ecclesial context, in its best is in-depth Bible study and at its worst is education by osmosis and observation. What is the call or consideration of the church to the topic of education? What role does the church have in the education of the community?

Most Americans share a common understanding that many public schools in poor neighborhoods aren’t great. It’s rare that I engage anyone who doesn’t know this basic fact on some level. But what’s less common is a deeper understanding of the extent of the problem. And sadly, even less common than that? Finding individuals who express a deep conviction that educational inequity can be eliminated. Faith communities are poised to add our voices to this much-needed conversation.

Fifteen million children live in poverty in the United States. Given poverty’s impact, many of these children already face additional challenges in their lives. For many young people, education can be “the great equalizer.” A high quality school can provide students with the necessary foundation to go to college and have a variety of opportunities opened to them. Poverty can become a thing of the past. But students growing up in poverty are more likely to attend low-performing public schools. In fact, only 22 percent of children who have lived in poverty do not graduate from high school. Only 9 percent receive college diplomas. And, not surprisingly, given our nation’s historical intersection of racial injustice and poverty, African American, Latino, and Native American students experience some of the nation’s biggest educational inequities.

Over the last few years we have heard much about the school to prison pipeline. According to the ACLU, it is:

a disturbing national trend wherein children are funneled out of public schools and into the juvenile and criminal justice systems. Many of these children have learning disabilities or histories of poverty, abuse or neglect, and would benefit from additional educational and counseling services. Instead, they are isolated, punished and pushed out.

The Children’s Defense Fund argues that because of a lack of early childhood education and healthy beginnings, this epidemic begins before a child is old enough to enroll in school, defining the problem as the Cradle to Prison pipeline. Organizations such as the Advancement Project, the Legal Defense Fund, and many others too have defined the school-to-prison pipeline as just another level to the mass incarceration epidemic and one of the most disturbing injustices we face today.

We know that the pipeline is undergirded by Zero Tolerance policies, mass expulsions, unprecedented school arrests, inadequate school funding, and myriad other unjust policies that either criminalize our children or rob them of the resources they need to be successful. We also know that high-school dropout is certainly a station on the pipeline. In many urban centers the dropout rate hovers around 50 percent, and some data suggests 7,000 students drop out of school every day. What happens to kids that drop out of school? Where do kids who are expelled end up?

They taught English, gym, music, and fifth grade, and are typically described as “beloved” by their students.

But that didn’t stop the Catholic schools where they worked from firing these teachers for their same-sex relationships, or, in one woman’s case, for admitting that she privately disagreed with church teaching on gay marriage.

A recent spate of sackings at Catholic institutions — about eight in the past two years — is wrenching for dioceses and Catholic schools, where some deem these decisions required and righteous, and others see them as unnecessary and prejudicial.