Social Justice

Listen in as Jim Wallis and Sojourners CEO Rob Wilson-Black kick off the new year with a discussion on Pope Francis and the new Pope's influential presence in all kinds of media.

Dozens of Catholic leaders are protesting the decision by the Catholic University of America to accept a large donation from the foundation of Charles Koch, a billionaire industrialist who is an influential supporter of libertarian-style policies that critics say run counter to church teaching.

Charles Koch and his brother, David, “fund organizations that advance public policies that directly contradict Catholic teaching on a range of moral issues from economic justice to environmental stewardship,” says a four-page letter to CUA President John Garvey, released Monday.

The letter was signed by 50 priests, social justice advocates, theologians, and other academics, including several faculty at CUA in Washington.

The U.S. Senate has confirmed former Catholic Relief Services head Ken Hackett to be the next ambassador to the Vatican.

Hackett replaces Miguel Diaz, a theologian, and he gives President Obama an experienced voice on social justice in Rome where a new pope, Francis, has made caring for the poor a priority.

Hackett’s confirmation came Thursday night by unanimous consent as senators wrapped up loose ends before the summer recess.

No opposition was expected since Hackett has strong ties to both parties; for five years he served on the board of former President George W. Bush’s Millennium Challenge Corporation and he is reported to be close to Denis McDonough, Obama’s chief of staff, whose brother is a priest.

THE LEADERSHIP of 12Stone Church, a multi-campus congregation based in Gwinnett County, Ga., became increasingly concerned about how home foreclosures, rampant unemployment, and other financial strains were impacting families in metro Atlanta. They set an ambitious goal of providing relief to 5,000 families in their church and community. Eventually they raised more than $550,000 through designated gifts, many from church members who were themselves unemployed.

Partnering with the HoneyBaked Ham Company, Kroger grocery stores, and other area sponsors, the 12Stone Church members distributed food to needy families, culminating with a day of giveaways in the parking lot of Coolray Field, home to the Gwinnett Braves, the local minor league baseball team. People began lining up hours before the event, jamming traffic on nearby I-85. Others slept in their cars overnight to keep from missing out.

Imago Dei Church in Raleigh, N.C., has mercy ministries built into the DNA of the church. They’ve adapted Rick Warren’s PEACE Plan: plant churches, evangelize the world, aid the poor and sick, care for the orphan and the oppressed, and equip leaders.

Working through the Raleigh-based nonprofit Help One Now, Imago Dei is partnering with an orphanage in Haiti and sponsoring children. Through this ministry, the church is providing basic needs, including food, clean water, and health care. They also support education programs so that the children will be equipped to one day provide for their own families.

Our church is right in the heart of the city and as such, many who make their home outside find their way into our worship services on Sunday and throughout the week for various reasons. The first year Amy and I were here, we made a concerted effort to allow people to sleep on the steps and in the courtyard of the church if they so chose, as it seemed to be the bare minimum offering of hospitality required of us.

In the past few months, however, things have gotten a lot more complicated. Several fights have broken out over turf, a couple of people have fallen and lost teeth or broken ribs, and at least three times, people have broken into the boiler room to sleep. At least once or twice a week, we catch a group of younger folks shooting up heroin in the courtyard, their needles scattered about in the midst of the greenery. We have found every kind of bodily waste one cares to imagine in the common area, and this Sunday during our annual church cookout, I had to escort one man out of the restroom for masturbating to pornography in one of the bathroom stalls.

There comes a point when the hospitality afforded to those we are trying to welcome in has to be weighed against the safety of those already present in the community. Although the sanitation issues and the vandalism were less than pleasant, the violence, drug use, and sexual indiscretions finally pushed us over the line. We met with the Portland police and had a notice posted that said any loiterers who refused to leave upon request would be arrested.

Pope Francis quickly is establishing himself as the “peoples’ Pope.” He has actively advocated for the poor, downplayed his elevated status, and speaks in colloquial terms that make him seem that much more human. He has left open the possibility that non-Catholics, non-Christians, and even atheists may fall within the vast embrace of a radically loving and merciful God. And now, he’s even made what many consider at least a benign – if not affirming – statement about homosexuality.

Historically, popes have toed an ideological line, asserting that homosexuality is inherently evil, and that all gay people are fundamentally disordered. In an expression of sincere humility, political savvy, or perhaps some combination of both, Francis took a more compassionate position, adding at the end of his comments, "who am I to judge?"

Welcome to the 20th century, Catholic Church.

The more I study theology and the more I take Jesus' teachings seriously, the more messy my life becomes.

I was raised to believe that Christianity is about going to church on Sundays, not saying bad words, trying to be good, and having all the right beliefs (and knowing who doesn't have the right beliefs). Within this framework, Christianity is very neat and proper. One dresses in such a way that conforms to modesty (no tattoos and piercings, thank you); one uses coined phrases to know who's really in or out (we say 'blessed' not 'lucky'); one never touches a cigarette or consumes alcohol (because that's what makes us 'not of this world' right?); and one makes sure to only hang out with those who have the same beliefs (for having different beliefs or opinions is clearly a sign of waywardness). This was my world all the way into my 20s.

Then something happened. Or, in actuality, many things happened. I am unable to pinpoint one thing that upended my world. It was a bunch of little and big things that projected me onto a path of radical living, and I give the credit to the Holy Spirit (and to my husband, but that's another story).

As a result of those many little and big things, I began to see the teachings of Jesus and the New Testament in new light. Passages I had heard all my life took on a whole new and radically different meaning. Beliefs I had taken on without thinking came crashing down, as I began to hold them in view of Christ's teachings. It was then I started to discover how far off my thinking, and thus my life orientation, was.

Making an ultimatum about church attendance to a sleep-deprived teenager may be my own version of hell on earth.

“We are leaving for church in 10 minutes,” I said, summoning my most authoritative voice before the lifeless lump under the covers.

My seven-year old Annie Sky watched the tense exchange between me and my 14-year old daughter Maya, who made periodic moans from the top bunk. With furrowed brow, my first grader sat on the couch, as if observing a tiebreaker at Wimbledon with no clear victor in sight.

For a moment, I wondered why I had drawn the line in the Sabbath sand, announcing earlier in the week that Maya would have to go to church that Sunday morning after an all-day trip to Dollywood with the middle school band. Somehow I didn’t want Dolly Parton’s amusement park to sabotage our family time in church. (The logic seemed rational at the time).

When Maya lifted the covers, I glimpsed the circles under her eyes and sunburn on her skin. But I repeated my command, with an undertone of panic, since I wasn’t sure if I could uphold the ultimatum.

When she finally got into the car, I breathed deeply and turned to our family balm, the tonic of 104.3 FM with its top 40 songs that we sing in unison. As the drama settled, I realized one reason why I made my teenager go to church: I want my daughters to know that we can recover from yelling at each other (which we had) and disagreeing. We can move on, and a quiet, sacred space is a good place to start.

The television flashes images of a skeletal little girl whose ribs seem to be popping out of her ballooning stomach as she sits in a pile of mud and stares at the camera with large pleading eyes. A “1-800” number flashes on the bottom of the screen. A celebrity does a Public Service Announcement for building wells in Africa. YouTube has sharp pre-packaged videos pulling at our heartstrings, and even months after being released, the KONY 2012 viral video continues to float around the internet.

For Westernized cultures saturated with various forms of media and technologically driven information, social justice is becoming increasingly "packaged," carefully marketed, and commercially manufactured to be a product that incorporates the mission it represents.

Whether social justice organizations should be doing this is debatable. Like everyone else, they’re trying to survive in a capitalistic system that ruthlessly competes for our every dollar. The only problem is that we aren’t the ultimate consumers. For social justice non-profit groups, the sick, poor, starving, abused, and desolate are the true consumers; we’re just the financial and volunteer base needed to keep the system working. To do this, organizations are discovering that a corporate business model is sometimes the only way to survive — and sometimes thrive — within the cutthroat world of advertising and solicitation.

On April 11, 1963 Pope John XXIII published an encyclical some initially dismissed as naive and myopic, as too liberal and too lofty. But today, his "Pacem in Terris" is generally lauded as genius and prophetic – well ahead of its time on the issues of human rights, peace, and equality.

As Maryann Cusimano Love, a Catholic professor of international relations, notes, the same year “Pacem in Terris” was published, spelling out the theological mandate for political and social equality for all people, women in Spain were not allowed to open bank accounts, Nelson Mandela was standing trial for fighting apartheid, and Walter Ciszek was serving time in a Soviet gulag simply for being Catholic.

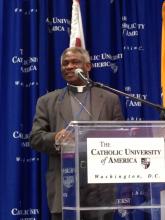

On Monday and Tuesday, the Catholic Peacebuilding Network hosted a two-day conference at the Catholic University of America, commemorating 50 years since the publication of "Pacem in Terris.”

While everyone was blowing up the Twittersphere decrying the injustices of the Oscars, as movies like Argo walked away with Best Picture honors, I was sitting in a Philadelphia hotel lobby trying to chew on everything I’d heard and seen at this year’s Justice Conference.

The two-day event brought together more than 5,000 people to promote dialogue around justice-related issues, like poverty and human trafficking; featured internationally acclaimed speakers such as Gary Haugen, Shane Claiborne, and Eugene Cho; and exhibited hundreds of humanitarian organizations.

While there is certainly more thinking and processing to be done, here are four things that stood out.

“You’re a Christian? But you’re so nice!”

I’ll never forget these words, spoken to me by a friend of mine from my college’s theatre program. He was one of my more eccentric friends, more blunt than most, and he was also very openly gay. His exclamation of surprise may be the instance that I remember the most, but he certainly wasn’t the only person during my college years to express their surprise at the thought of Christians living by principles of love rather than intolerance, or at the very least, indifference.

I don’t know about you, but I’m pretty sure I have sung “O Little Town of Bethlehem” every year on Christmas Eve for my entire life. But I believe this carol’s lyrics, specifically the words of the first verse, invite a little more thought than we normally give them.

O little town of Bethlehem

How still we see thee lie

Above thy deep and dreamless sleep

The silent stars go by

Yet in thy dark streets shineth

The everlasting light

The hopes and fears of all the years

Are met in Thee tonight

For now let’s ignore the historical inaccuracies of the song, and focus on what the words mean, especially the last four lines. How beautiful is it that through the dark world a light came to bind together the hopes and fears of all the years (I choose to see it as past and future) in Jesus?

I had a conversation with a young woman I met at a conference recently. The conversation rocked me.

I represented the faith voice on a panel at a major secular conference for philanthropists. The panel focused on the question: “What are we not talking about?”

One of my colleagues focused on the nonprofit sector’s inability to make real just change in our world because they are bound by the interests of donors who are, themselves, part of the 1 percent. Another colleague focused on the glut of nonprofits offering similar services in otherwise abandoned communities. I focused on the need for social movements to bring about a more just world and the role of faith communities in those movements, in particular.

As the assistant humanist chaplain at Harvard University, Chris Stedman coordinates its “Values in Action” program. In his recent book, Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious, he tells how he went from a closeted gay evangelical Christian to an “out” atheist, and, eventually, a Humanist.

On the blog NonProphet Status, and now in the book, Stedman calls for atheists and the religious to come together around interfaith work. It is a position that has earned him both strident -- even violent -- condemnation and high praise. Stedman talked with RNS about how and why the religious and atheists should work together.

Some answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What does the term “faitheist” mean? Is it a positive label or a derisive one?

A: It's one of several words used by some atheists to describe other atheists who are seen as too accommodating of religion. But to me, being a faitheist means that I prioritize the pursuit of common ground, and that I’m willing to put “faith” in the idea that religious believers and atheists can and should focus on areas of agreement and work in broad coalitions to advance social justice.

The recently revealed video of Gov. Mitt Romney at a fundraising event last May is changing the election conversation. I hope it does, but at an even deeper level than the responses so far.

There are certainly politics there, some necessary factual corrections, and some very deep ironies. But underneath it all is a fundamental question of what our spiritual obligations to one another and, for me, what Jesus' ethic of how to treat our neighbors means for the common good.

Many are speaking to the political implications of Romney's comments, his response, and what electoral implications all this might have. As a religious leader of a non-profit faith-based organization, I will leave election talk to others.

“In order to serve our world," Bono once said, "we must betray it."

I’ve always wanted to change the world. I’m inspired by stories of people who have left their fingerprints on the very face of culture. I want to be a historymaker. I want to be one who people remember as a person who revolutionized her world.

As noble as this sounds, I’m afraid that up until a few years ago, this has come from a very self-serving motivation. I truly did want to love people and make a difference for their benefit, but I also wanted the credit. Visions of winning a Nobel Prize danced through my mind; dreams of becoming the “woman of the year.” I’ve thought out speeches just in case.

I can’t believe I just admitted that to you. I must really like you.

I had to come to a broken place in order to be ready to bring about the change I so desired to initiate. You see, transformation, no matter how small or big, is never about us. It’s not about the recognition we will receive or about the merit badge that will feed your need for approval. No, it’s the most selfless thing we will ever do. We need to be trustworthy to lead such efforts.

All it takes is a heart that truly cares for others — that’s it. Once your eyes are off yourself, you become incredibly useful! What a thrill it is to add benefit to others and get no credit for it.

On Aug. 17, three members of the Russian feminist punk band/performance art group Pussy Riot received the verdict in the criminal case against them: Guilty of "hooliganism" motivated by "religious hatred." Each was sentenced to two years in prison.

As a faith-based community organizer, I spend a great majority of my time trying to get political issues into the church so that the gospel can be relevant to the reality of those on and off the pews.

Therefore, I believe the best place for a “pussy riot” is the church. Although this may seem sacrilegious, here's why:

1. When the church ignores social and political issues it silently blesses injustice. (See slavery, the Holocaust, lynching, and child sexual abuse.) Testimony Time is a set time in many Black Churches when congregants can speak of their pains and triumphs and how God brought them through.

Testimony time is democratic and a time of raw honesty. I call what Pussy Riot did protestifying because they protested by testifying about the political conditions of their country.

Near the turn of the 2nd century A.D., the poet Juvenal published a collection of verses titled Satires. Among other things, the text was intended to spark discussion about social norms at a time when the masses were increasingly withdrawn from civil engagement.

In specifics, Juvenal wrote:

…everything now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses.

According to Juvenal, the public of his day and age was growing less concerned about social responsibility due to personal pursuits of bread (comfort) and circus (entertainment). In addition, he believed political leaders used the distribution of comfort and entertainment as a way to sedate the population, distract them, and open opportunities for systemic manipulation.

Juvenal believed far too many citizens were far too willing to cooperate in their own exploitation.

What I find incredibly intriguing — and disconcerting — about Juvenal’s observations is that, numerous generations later, it can be argued that much of what he considered to be problematic in his era can now be found in North America.