Reggie L. Williams is associate professor of Christian Ethics at McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago and author of Bonhoeffer's Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance.

Posts By This Author

Is This a Bonhoeffer Moment?

Lessons for American Christians from the Confessing Church in Germany.

Are we in a “Bonhoeffer moment” today?

It is common to wonder what we would have done if we lived in history’s most challenging times. Christians often find moral guidance in the laboratory of history—which is to say that we learn from historical figures and communities who came through periods of ethical challenge better than others. Christians who wish to discern faithfulness to Christ often look back to learn how others were able to determine faithful discipleship when their contemporaries could not.

With this in mind, Dietrich Bonhoeffer may help us out today.

Bonhoeffer was a German theologian and pastor who resisted his government when he recognized, very early and very clearly, the dangers of Hitler’s regime. His first warning about the dangers of a leader who makes an idol of himself came in a radio address delivered in February 1933, just two days after Hitler took office.

The Fringe Is the Majority

Like many people in the nation, I was deeply disturbed when I stayed up late watching the election results on Nov. 8. This country elected Donald Trump to succeed the nation’s first African-American president — a deed that was in no way coincidental. President Obama’s election was an historic moment: the United States sent a black family to live in the house that slaves built as a residence for the highest political office in the land of their captivity. And with the election of Obama to that high office, the White House became home to free ancestors of the slaves who built it. Obama’s election felt like an earthquake of sorts. When the dust settled, it seemed that some old, terrible things had been demolished, and other things were moved around. From all appearances society had been recalibrated.

How the Construct of Race Deforms Our Understanding of Christ

Christian communities get romanticized as places populated with ideal human beings who reflect a pursuit of individual morality in a community of righteous individuals. Yet, in a society organized by race, ideal humanity is always white. Race has calibrated dominant streams of Christianity according to the goals of white supremacy rather than allowing the gospel to calibrate human social interaction toward justice. Christianity scrubbed of justice turned Jesus into a white man, and the gospel into a message of individual morality, calibrated to the language of virtue derived from Jesus as a fetish of idealized white masculinity.

Christian America's Constant Struggle with a 'Thinned-Down' Jesus

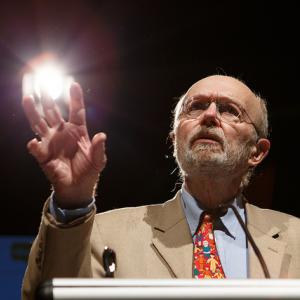

Remembering Christian Ethicist Glen Stassen

Glen Stassen. Danske Kirkedage / Flickr.com

I knew that the problem of race in America was one of the two main engines that mobilized his project in Christian ethics. The other was the threat of war. In the 1980s, Glen put together a method of doing Christian ethics in the context of the Cold War that was meant to help foster clarity in conversation and allow unspoken influential preferences to be recognized. As he understood it, we are much more than reasoning, rational minds; we are a complex amalgam of different contributing factors, including our core convictions, community loyalties, things we are passionate about, people we trust, and political commitments. Indeed, many things are at play in all of our ethical decisions.

Harlem's Influence on Bonhoeffer Underestimated in 'Strange Glory'

Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer is the second Bonhoeffer book by the University of Virginia religion scholar, Dr. Charles Marsh, whose many other books include analyses of civil rights figures and history. Marsh is himself a child of the south, and his authored works have centered on prominent figures who model a commitment to justice in the face of southern white supremacy. Strange Glory is no different. Marsh’s depiction of Bonhoeffer is the first cradle-to-grave biography to highlight the seminal nature of Bonhoeffer’s experience in America, with African Americans, for his prophetic resistance to Nazism. Marsh also speculates that Bonhoeffer harbored an unrequited longing for more than friendship from his student and closest friend, Eberhard Bethge. Yet, with Strange Glory, I find speculation about Bonhoeffer’s sexuality less intriguing than the question of what Marsh’s representation of Bonhoeffer intends to offer us today.

Bonhoeffer spent a significant amount of time in Harlem while he was a postdoctoral student in America at Union Theological Seminary during the 1930-31 school year. Bonhoeffer became a lay leader at Abyssinian Baptist Church, and many Bonhoeffer scholars believe that his time there was seminal for his prophetic Christian resistance to Nazis. Yet Bonhoeffer’s relationship with Harlem is somewhat ambiguous for the Bonhoeffer that Marsh constructs. Instead, he emphasizes Bonhoeffer’s travels through the Jim Crow South, positioning the south (or, southern blackness) over against the north or northern, Harlem blackness as the primary source of African-American Christian influence on Bonhoeffer.

In fact, Harlem blackness gets a bad rap in Marsh’s Bonhoeffer story with this juxtaposition of southern vs. northern blackness.

Bonhoeffer's Harlem Renaissance

Excerpt from "Bonhoeffer’s Black Jesus: Harlem Renaissance Theology and an Ethic of Resistance," by Reggie L. Williams

During his 1930-31 fellowship at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, German theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer joined his African American classmate Albert Fisher as a regular attendee at Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem.

WHEN BONHOEFFER entered Harlem with Fisher, he met a counternarrative to the white racist fiction of black subhumanity. The New Negro movement radically redefined the public and private characterization of black people. A seminal moment in African American history had arrived, and all of Bonhoeffer’s descriptions of his involvement in African American life during his Sloane Fellowship year occurred during this critical movement. He turned 25 that February. Bonhoeffer was experiencing that critical moment in African American history while he was still young and impressionable.

The New Negro, a book containing a collection of essays, was edited by one of the leading intellectual architects of the movement, Alain Locke. The New Negro, as Locke and his authors appropriated the term, described the embrace of a contradictory, assertive black self-image in Harlem to deflect the negative, dehumanizing historical depictions of black people. The New Negro made demands, not concessions: “demands for a new social order, demands that blacks fight back against terror and violence, demands that blacks reconsider new notions of beauty, demands that Africa be freed from the bonds of imperialism.” Bonhoeffer knew the movement by the descriptor New Negro, but James Weldon Johnson preferred to describe the movement as the Harlem Renaissance ... as a rebirth of black people rather than something completely new. ...