Interfaith

A statement by a group of Orthodox rabbis calls Christianity part of a divine plan in which God would have Jews and Christians work together to redeem the world.

Although signed so far by 28 rabbis mostly from the more liberal wing of the most traditional branch of Judaism, the statement marks a turning point for Orthodox Jews, who until now have limited interfaith cooperation to working on social, economic and political causes. But this statement puts Christianity in a distinct Jewish theological perspective — and an extremely positive one.

“(W)e acknowledge that Christianity is neither an accident nor an error, but the willed divine outcome and gift to the nations,” the seven-paragraph statement, issued on Dec. 3, asserts.

As October quickly turned to November, jack-o-lanterns and costumes were replaced by Christmas carols and Internet outrage over holiday cups. Every year we go from Halloween to Christmas with little space carved out for Thanksgiving.

There is no question that Thanksgiving is my favorite holiday. Many times I have remarked that Thanksgiving is one of the greatest days of the year, that I cannot wait to go home, that Christmas needs to wait until December. Come every November, I begin my internal countdown, growing more excited each day closer to this holy holiday.

We often reserve the word “holy” for holidays such as Christmas and Easter, but for a multi-faith family such as my own, a holiday grounded in something more substantial than – let’s say trees for Arbor Day – while still allowing everyone to come with their own religious identity is not only a privilege, but a gift.

Hamtramck, Mich. residents have elected a Muslim majority to its city council, symbolizing the demographic changes that have transformed the city once known for being a Polish-Catholic enclave.

In Tuesday’s election — with six candidates running for three seats — the top three vote-getters were Muslim, while the bottom three were non-Muslim. Two of the Muslim candidates, Anam Miah and Abu Musa, are incumbent city councilmen, while newcomer Saad Almasmari, the top vote-getter, was also elected. Incumbent City Councilman Robert Zwolak came in fifth place.

Some believe the city is the first in the U.S. with a Muslim majority on its city council.

When a half-dozen activists and community leaders sat down to address interfaith relations in the increasingly diverse heartland city of Nashville, Tenn., one paused before his turn to speak, took a breath and said:

“As a white, male, evangelical pastor on this panel, I guess I represent everything that is wrong.”

The speaker, Joshua Graves, the 36-year-old senior pastor of Otter Creek Church, an 1,800-member suburban megachurch, had a point. Evangelicals like him have had a rocky relationship with American Muslims.

But then again, he may also represent everything that could be right in Christian-Muslim understanding.

They can be found on the battlefield, at a chicken-processing plant, and behind the locked gates of a prison.

They are chaplains, and as a two-hour, two-part documentary airing on PBS stations beginning Nov. 3 points out, they minister to people of all religions and none in places where they work and live.

“Their ministry really does bring them into some of the most extraordinary places where people are in crisis and need,” said Journey Films producer/director Martin Doblmeier in an interview.

It’s hard to stand in front of a congregation and talk about domestic violence.

It’s hard, because you never really know the stories of the people sitting there.

Who might have experienced domestic violence in their lives, in their home growing up, in a relationship during high school, on a college campus, in the home where they now reside?

Who might have experienced it last night? Who might have been told by their mother or religious leader that they cannot leave an abusive marriage because they would be breaking their vows? Who might have struck out at a partner? Who might have let their needs for control overwhelm their sense of self-restraint? Who might want to mask their violence with a smile or generous donations?

It's hard to stand in front of a congregation and talk about domestic violence. But it’s essential.

It’s essential because too often in the past, religious traditions have been used to defend an abusive patriarchy, to bind victims to marriage commitments that are undermined by intimate violence, to encourage people to “offer up” suffering rather than change the conditions that cause it.

It’s essential because shining a light of the reality of domestic violence is a critical step in creating pathways to safety for those who are victims. It’s essential because speaking out about domestic violence as a violation of God’s love can give victims strength to seek a better way. It’s essential because naming domestic violence as evil can help call perpetrators to account – and perhaps to repentance and treatment.

My rabbinic colleague, David Saperstein, the U.S. ambassador-at-large for international religious freedom, issued a “glass half full” report earlier this month, noting that “… over the last several years there’s been a steady increase in the percentage of people who live in countries that … have serious restrictions on religious freedom.”

At the same time, he noted, “we’ve seen enormous expansion of interfaith efforts on almost every continent to try and address the challenges.”

Much of that “enormous expansion of interfaith efforts” can be traced to the historic Nostra Aetate (Latin for “In Our Time”) Declaration that the world’s Catholic bishops adopted 50 years ago at the conclusion of the Second Vatican Council.

A majority of evangelical pastors consider Islam to be “spiritually evil,” according to one just-released poll, but on Oct. 23 an evangelical pastor and an imam took turns talking about their friendship and mutual respect.

Texas Pastor Bob Roberts and Virginia Imam Mohamed Magid joined dozens of other religious leaders in prayer at the Washington National Cathedral before signing a pledge to denounce religious bigotry and asking elected officials and presidential candidates to join them.

“I love Muslims as much as I love Christians,” said Pastor Bob Roberts, of Northwood Church in Keller, Texas, before leading a prayer at the “Beyond Tolerance” event.

“Jesus, when you get hold of us, there’s nobody we don’t love.”

A commitment to interfaith dialogue is important, but not simply for its own sake or to admire each other’s diversity. Interfaith dialogue should be in service of these three goals, especially for the sake of those who are the most vulnerable in our society and around the world — exactly who our faith traditions agree we should be most concerned about.

This will be the true test of a moral global economy. We convene our religions to celebrate diversity. Can we also convene our religions to help end extreme poverty by 2030 — and end shameful poverty in the United States? That would certainly be a goal worthy of a Parliament of World Religions.

When the World’s Parliament of Religions first met in Chicago in 1893, Christians, Jews, Hindus, Buddhists, Muslims, and even Spiritualists prayed together.

But Mormons were kept out.

What a difference 122 years make. On Oct. 15, when the Parliament of the World’s Religions — a slight adjustment of the name was made a century after the first meeting — convenes in Salt Lake City, it will not only feature a slate of Mormon voices, it will sit in the proverbial lap of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, its global headquarters only a five-minute walk away.

Two of North America’s most liberal Protestant church groups have teamed up and agreed to recognize each other’s members, ministers, and sacraments.

The United Church of Christ and the United Church of Canada will celebrate their full communion agreement on Oct. 17 at a church in Niagara Falls. Leaders from the two denominations will sign the agreement during the service.

Full communion means the two denominations will recognize each other’s members, ordained ministers, and sacraments.

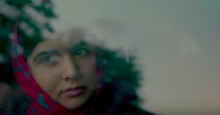

The story of Malala Yousafzai is well beloved by Western media, with news outlets having followed her life closely for the past three years. And rightly so. The Pakistani teen is an activist for girls’ education and a well-respected world leader in promoting the voices of women and girls around the globe.

It was her belief that all girls have a right to an education that made her a target of the Taliban, resulting in Malala losing hearing in her left ear and being forced out of her beloved home in the Swat Valley, Pakistan. Malala celebrated her sixteenth birthday by addressing the United Nations in 2013, the same year she released her memoir, I Am Malala. And most recently, she was named the Nobel Peace Prize recipient of 2014. Her non-profit, The Malala Fund, invests and advocates for girls’ secondary education, in order to amplify the voices of girls around the world who have been ignored.

It would be hard to create a stronger superhero for girls and boys in anyone’s imagination.

Pope Francis embraced survivors of 9/11 in the footprints of the Twin Towers, then prayed for peace at an interfaith service beside the last column of steel salvaged from the fallen skyscrapers.

Arriving straight from his speech to the United Nations on Sept. 25, Francis met with 10 families from the 9/11 community — people who survived the destruction, rescued others from the inferno, or lost loved ones in the worst terrorist attack in U.S. history, executed by religious zealots.

An interfaith group gathered in a private home Sept. 21 to head off potential tensions over how Jews and Muslims celebrate Yom Kippur and Eid al-Adha, two holidays that overlap this year.

The meeting of the Abrahamic Reunion took on added significance in Jerusalem, where more than a week of violent clashes between Israelis and Palestinians on the Temple Mount have spilled into the streets of East Jerusalem.

Two dozen people of various faiths heard a rabbi explain the laws and traditions of Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, and a Muslim sheikh explain the laws and traditions of Eid al-Adha, the Muslim holiday that honors the willingness of Ibrahim (the biblical Abraham) to heed God’s order to sacrifice his son.

The day culminated with an interfaith peace walk between the eastern and western parts of the city. Israel captured East Jerusalem in 1967 and considers it part of its capital. The Palestinians say East Jerusalem must be the capital of a future Palestinian state.

THIS YEAR MARKS the 50th anniversary of the Vatican II document Nostra Aetate, the 1965 proclamation on “the relation of the church with non-Christian religions.” I want to celebrate a great theologian whose life intersects with that moment and whose work exemplifies its ethic.

Paul Knitter grew up in a strong working-class Catholic family on the South Side of Chicago and felt the call to the priesthood in his early teens. After four years of seminary high school and two years of additional novitiate training, he joined the Divine Word Missionaries (or SVD), an order whose main work was bringing non-Catholics into the Catholic faith. His regular prayers included the line “May the darkness of sin and the night of heathenism vanish before the light of the Word and the Spirit of grace.”

Reflecting back on this practice in his book One World, Many Religions, Knitter writes: “We had the Word and Spirit; they had sin and heathenism. We were the loving doctors; they were the suffering patients.”

Knitter’s journey took a number of unexpected turns. As he sat with the other seminarians listening to the stories of returned SVD missionaries, he discovered that he was fascinated by the slide shows of Hindu rituals and Buddhist ceremonies. He even detected a hint of admiration in the voices of older SVD priests as they described the elaborate non-Christian religious systems that they encountered on their missions. One brought in an Indian dance group and explained that their performance was developed in a Hindu context but had been adapted to glorify Jesus. Knitter was entranced by the intricacy of the movements, and he found himself wondering whether “sin and heathenism” were the correct terms for a tradition that could inspire such beauty.

On the eve of Yom Kippur and Pope Francis’ arrival to the United States, more than 100 Christian, Muslim, and Jewish faith leaders gathered at the National Press Club to participate in the Interfaith Religious Leaders Summit: End Hunger by 2030, hosted by Bread for the World. Participants shared a meal around tables as they reflected on their faith traditions around hunger and poverty, discussed how to best achieve a positive shift in U.S. national priorities by 2017, and publicly committed themselves and their faith communities to help end hunger by 2030.

The summit began with a reception during which everyone — from heads of churches to CEOs of faith-based organizations — shared introductions with new partners and reunited with old friends. Rev. Carlos Malavé of Christian Churches Together greeted everyone with a welcome.

“Tonight we come together as people of faith. If we gather together, as we are tonight, and we commit to each other in this task, we will certainly achieve everything that God is calling us to do,” he said.

Faith communities have long been at the forefront of dynamic and significant change, and they’ve been a driving force behind global efforts in response to ebola, in combating HIV/AIDS, and in famine relief, to name just a few. From Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., to the Dalai Lama, people of faith have helped create and sustain social movements — and have recognized the responsibilities that faith bestows.

Christians, Buddhists, Muslims, Jews, and Hindus may all express their religious faith in different ways, but each community shares its beliefs, seeks salvation, and opens its heart through its own moments of reflection and in its own places. We live in the same world — under the same sky — and, because of our shared humanity and faith, we share many of the same hopes and fears.

That’s the instinct behind the "Prayer for Everyone" movement, which we at ONE have been working on with other partners in the Project Everyone coalition.

Extremist groups like ISIS and Al Qaida are trying to radicalize young Muslims through well-produced and elaborate online videos and sweeping Twitter campaigns targeted at disaffected young men and women around the world.

Three London school girls recently ran away to join ISIS in Syria after encountering recruiters on Twitter. A Sunday school teacher in Washington state secretly converted to Islam and planned to leave home to join the only Muslims she knew — Isis recruiters she encountered through social media. In Virginia, a local imam meets with young men and women whose families fear they will answer the call of ISIS sent through their cellphones.

As one member of the local law enforcement told our group of 17 international journalists, “There is a terrorist in your pocket and it is talking to you all the time.”

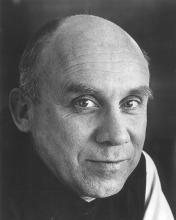

If the influential Catholic writer Thomas Merton were alive today, he would likely have strong words about police brutality and racial profiling.

Back in 1963, Merton called the civil rights movement “the most providential hour, the kairos not merely of the Negro, but of the white man.”

His words echoed May 16 among black pastors at a conference, titled Sacred Journeys and the Legacy of Thomas Merton, hosted by Louisville’s Center for Interfaith Relations. The event marked the 100th anniversary of Merton’s birth.